We Don’t Have Private Property in the West: Overtaken from the Start

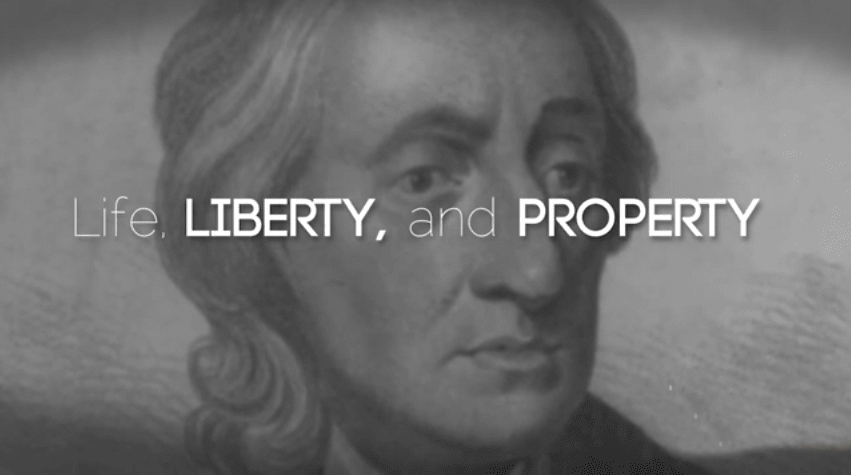

In America, the idea of owning property—a home, a piece of land—feels like a bedrock of freedom. But the reality hits hard if you fall behind on property taxes: the government can take it away, turning what seems like true ownership into something more like a long-term lease. This wasn’t the vision of the Enlightenment thinkers who influenced our founders. John Locke, the English philosopher whose ideas helped spark the Revolution, saw property as inseparable from life and liberty, arguing that governments exist mainly to protect it. Over time, though, this straightforward principle has been reframed and weakened, allowing taxes and regulations to chip away at it. The point here isn’t to upend the system but to strengthen it: property should be recognized as a core American right, explicitly protected in the Bill of Rights like freedom of speech or religion. And crucially, counties and cities shouldn’t fund themselves by taxing this fundamental right—they need to turn to other revenue sources that don’t undermine ownership.

Locke’s Guidestone and the Evolution of the Idea

Locke’s thinking evolved from earlier philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, who saw human nature as brutish and government as an absolute ruler to impose order. Locke offered a more hopeful view in his Two Treatises of Government (1689), where natural rights include property, gained through labor: “Though the earth, and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a ‘property’ in his own ‘person.’ This nobody has any right to but himself. The ‘labour’ of his body and the ‘work’ of his hands, we may say, are properly his” (Second Treatise, Chapter V, §27, pp. 18-20). He made property the cornerstone, stating that “the preservation of property [is] the end of government” (Second Treatise, Chapter VII, §85, pp. 40-42). On taxes, he allowed them for public needs but only with consent: “It is true governments cannot be supported without great charge… But still it must be with his own consent—i.e., the consent of the majority” (Second Treatise, Chapter XI, §140, pp. 70-72).

This was vital for early Americans. Just years before the Revolution, they were British subjects, taxed without representation under the Crown. The 1776 Declaration made them independent, and by 1790’s Naturalization Act, citizenship was defined for “free white persons of good character”—no longer subjects to a king, but sovereign citizens. Property rights embodied this shift, securing their new freedom from arbitrary power.

How America’s Founders Adapted—and Opened the Door to Change

The founders echoed Locke but made a key shift. In the Declaration of Independence (1776), Thomas Jefferson replaced “property” with “the pursuit of happiness,” drawing from sources like George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, which connected property to broader well-being. This change aimed for inspiration and unity, perhaps sidestepping slavery’s thorny implications, where people were treated as property. The founders likely viewed property rights as so essential they were implied, protected indirectly in the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment: no deprivation “without due process of law.”

Yet this ambiguity allowed later interpretations to erode protections. Some argue the Fifth Amendment suffices, offering procedural checks against unfair takings. But it permits property taxes and eminent domain as long as there’s process and compensation—falling short of Locke’s absolute safeguard. Others say taxes are vital for services, but alternatives like sales taxes on consumption, user fees, or income-based levies could fund localities without targeting ownership. These options, often progressive through exemptions, avoid the regressive impact on fixed assets.

This ties directly to the historical timeline of American identity, as explored in “What Does 1 Year and 9 Months Mean to an Ethnic American?” at https://ethnicamerican.org/what-does-1-year-and-9-months-mean-to-an-ethnic-american/. That piece highlights the 1 year and 9 months between the Naturalization Act of 1790—defining an American as a “free white person of good moral character”—and the Bill of Rights’ ratification in 1791. During that gap, citizens operated without enumerated rights, suggesting the Constitution was crafted for a specific group: free white men. “An Ethnic American was defined before our rights were enumerated,” the article notes. Just as citizenship was limited before broader protections, property rights have been reframed over time, diluting their role as a shield for those early Americans and their descendants.

The Evolution of Property Taxes and Their Modern Toll

Property taxes date back to colonial times, funding basics like roads and schools, and by the 19th century became value-based assessments. Today, they make up about 30% of local revenues, but they create a paradox: ownership depends on ongoing payments, turning property into a liability when values rise. Defenders point to stability and community benefits, but when taxes force sales, they contradict Locke’s purpose. Reforms like homestead exemptions or circuit breakers help some, but a full shift to non-property sources would better align with American rights.

Gentrification as a Case Study: Lessons from Los Angeles

Nowhere is this clearer than in urban gentrification, where tax hikes drive out longtime owners. In Los Angeles, neighborhoods once farmland have transformed, displacing residents as values soar. Beverly Hills, starting as bean fields, boomed with Hollywood, leading to tax burdens that pushed out early families. Pacific Palisades followed suit, shifting from ranches to luxury homes post-1920s. From 1990 to 2015, 16% of LA tracts gentrified, with taxes exacerbating the squeeze in places like Highland Park.

Proponents say gentrification brings investment and better services, but it often comes at the expense of community stability, echoing how early American rights were tied to a narrow citizenship definition. When taxes enable this, they stray from protecting property as an American right.

Securing Property as a True American Right

The founders built a strong foundation, assuming property’s centrality. But as interpretations evolve, it’s time to reaffirm it explicitly in the Bill of Rights—insulated from overreach. By requiring localities to seek other revenues, we can honor Locke’s legacy and the timeline of our founding, ensuring property remains a secure American right for all who inherit this nation’s promise.

James Sewell 2025 – All rights reserved

@Jamestown_Son

13th generation Ethnic American – 1619 Jamestown

August 19, 2025

Pingback:The Road to Revolution - Ethnic American