I’ve written this article with one goal: to make the lead-up to the Declaration of Independence clear for every reader, no matter your schooling or background. I want to respect your intelligence while ensuring the story of America’s fight for freedom is easy to follow. Let’s dive into what pushed the colonies to declare independence in 1776, focusing on their lack of a voice in government, their desire for equal rights as British citizens, and the key events that set the stage for revolution.

In the mid 1700s, the American colonies found themselves increasingly at odds with British rule, setting the stage for one of history’s most pivotal declarations of self-determination. What began as simmering discontent over economic policies and governance evolved into a full-throated demand for independence, rooted in fundamental principles of rights, representation, and autonomy. Central to this tension was the colonists’ status as British subjects who were denied the full privileges of citizenship, including meaningful representation in Parliament. As British citizens in name, they sought the same rights enjoyed by those in England—such as participation in lawmaking and protection from arbitrary rule—but were treated as second-class entities, expected to fund the empire without a voice in its decisions. This lack of representation fueled outrage, epitomized by the rallying cry of “no taxation without representation,” which highlighted how colonists were burdened with taxes and regulations imposed from afar, without their consent or input.

Compounding this was Britain’s uneven approach to naturalization and immigration, which affected who could fully integrate into colonial society. For instance, the Plantation Act 1740 allowed Jews residing in the American colonies for at least seven years to naturalize and gain the rights of natural-born British citizens, notably without requiring Jews to take the Christian oaths. This act created disparities in who could achieve citizenship. While it facilitated integration for some immigrants, broader royal policies obstructed naturalization laws proposed by colonial assemblies, limiting population growth and reinforcing the sense that the crown prioritized control over equitable expansion. Colonists, many of whom were immigrants or descendants of immigrants seeking opportunity, viewed these restrictions as barriers to building prosperous, self-sustaining communities, further eroding loyalty to the king.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, the events culminating in 1776 were not primarily about a single tax on tea. The Tea Act of 1773, which actually lowered the duty on tea but granted a monopoly to the British East India Company, was merely a flashpoint in a much larger narrative of systemic oppression. The Boston Tea Party protest in 1773 and the subsequent punitive Intolerable Acts (known as the Coercive Acts in Britain) intensified conflicts, but the core issues stretched back decades, encompassing trade restrictions, military impositions, and judicial overreach. These grievances reflected a deeper struggle against perceived tyranny, where the colonies’ economic vitality was stifled to benefit the mother country.

The path to the Declaration of Independence was paved by earlier colonial responses that articulated these frustrations. One key precursor was the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, drafted by the Stamp Act Congress—a gathering of delegates from nine colonies in New York City—and adopted on October 14, 1765. This document protested the Stamp Act, which imposed direct taxes on printed materials without colonial consent, asserting that only colonial legislatures had the right to tax their inhabitants. It emphasized the colonists’ entitlements as British subjects, including trial by jury and representation, and petitioned the king and Parliament for relief. Though the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, the underlying principles of this declaration influenced ongoing resistance.

Building on this, the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress, adopted on October 14, 1774, escalated the colonial stance in response to the Intolerable Acts. These measures, which closed Boston’s port, altered Massachusetts’ government, and expanded quartering of troops, were seen as direct assaults on colonial liberties. The Congress, representing 12 colonies in Philadelphia, reaffirmed the rights of colonists to life, liberty, and property (which I wrote about in the Article, “Life Liberty and the Pursuit of WHAT?“), boycotted British goods, and called for unity against further encroachments. This document not only organized economic retaliation but also laid the ideological groundwork for separation, framing British actions as violations of natural rights and constitutional principles.

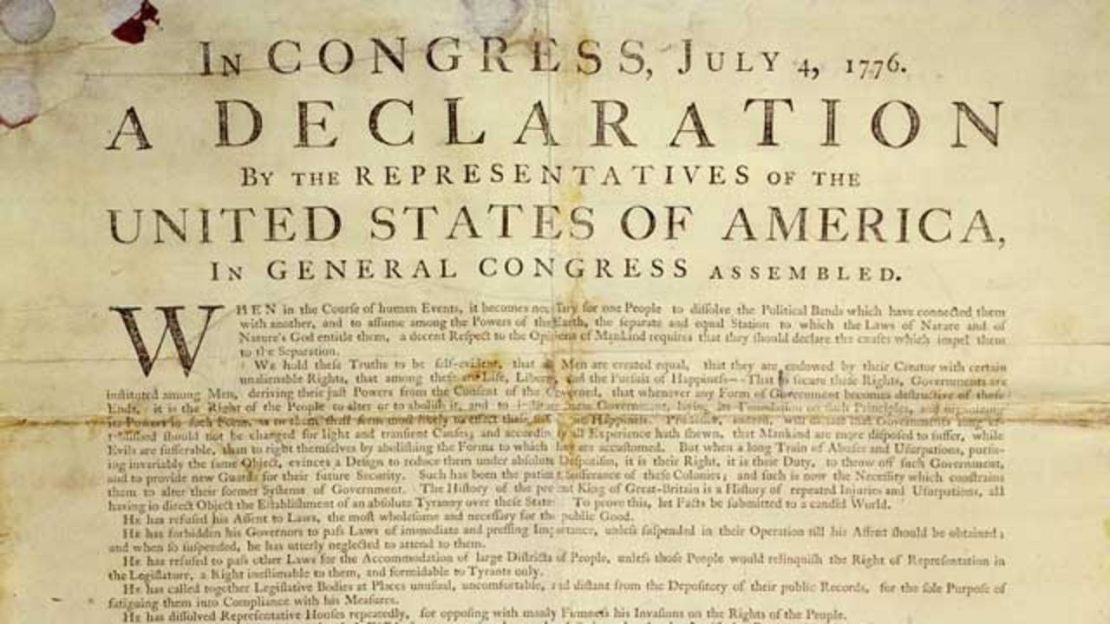

These earlier declarations directly informed the United States Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776. Notably, much of its language and philosophy drew from George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, ratified just weeks earlier on June 12, 1776, by the Virginia Convention. Mason’s document proclaimed inherent rights such as freedom of the press, religious liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which Thomas Jefferson echoed in the national declaration. As a direct descendant of George Mason, I hold a personal connection to this legacy, underscoring how individual visionaries shaped the collective fight for independence.

Together, these developments illustrate how years of unaddressed grievances— from fiscal exploitation to the denial of self-governance—propelled the colonies toward revolution. What follows is an enumerated breakdown of the 27 specific grievances outlined in the Declaration, translated by me into modern terms for clarity and an example of each grievance is provided.

Our Colonial Grievances

1. King George III has blocked laws that were beneficial and necessary for the public’s well-being.

- In the 1760s, colonial assemblies passed laws on trade, currency, and representation, but the king withheld approval, such as refusing a Massachusetts act in 1765 that would pardon rioters after compensating for Stamp Act damages, worsening tensions over self-governance.

2. King George III has prohibited his governors from passing urgent and important laws until he approved them, and when those laws were delayed, he completely ignored them.

- In 1770, the Massachusetts governor was ordered by the king not to approve a law taxing British officials, violating the colony’s charter and leaving critical issues like taxation unresolved, highlighting colonial powerlessness.

3 King George III has refused to pass laws benefiting large groups of people unless they gave up their right to representation in the legislature, a right they deeply valued and only tyrants would fear.

- Drawing from John Locke’s ideas, this grievance targeted the king’s arbitrary demands that colonists surrender legislative rights for basic accommodations, such as in frontier districts where representation was non-negotiable for fair governance in the 1770s.

4. King George III has forced legislative bodies to meet in unusual, inconvenient, and distant locations, far from their public records, just to exhaust them into agreeing with his policies.

- On May 20, 1774, under the Massachusetts Government Act, Governor Thomas Gage moved the assembly from Boston to Salem, making access to records difficult and pressuring compliance with British measures post-Stamp Act unrest.

5. King George III has repeatedly shut down representative assemblies for boldly standing up against his violations of people’s rights.

- In 1768, the Massachusetts Assembly was dissolved for urging other colonies against taxation without consent; similarly, Virginia’s House of Burgesses was disbanded in 1765 for resolutions against the Stamp Act, stifling colonial dissent. My 8th Great Grandfather Henry Sewell was a member of the Virginia House of burgess.

6. King George III has, for long periods after dissolving these assemblies, refused to allow new elections, leaving the people without legislative power and vulnerable to external attacks and internal chaos.

- From July 1768 to May 1769, Massachusetts went without an assembly after dissolution, facing military threats with cannons aimed at their meeting hall, exposing the colony to invasion risks amid growing unrest.

7. King George III has tried to limit population growth in the colonies by blocking laws that would make it easier for foreigners to become citizens, discouraging immigration, and making it harder to claim new land.

- Post-1763 Peace of Paris, the king restricted western settlements beyond the Alleghenies and obstructed naturalization for German immigrants, fearing republican ideals, which nearly halted immigration by the Revolution’s eve.

8. King George III has interfered with the justice system by refusing to approve laws needed to establish fair judicial processes.

- In 1774, Parliament stripped Massachusetts of electing judges, appointing them royally with salaries from colonial taxes, obstructing justice and denying jury trials under acts like the Massachusetts Government Act.

9. King George III has made judges dependent solely on his authority for their jobs and salaries, undermining their independence.

- In 1774, Chief Justice Oliver in Massachusetts drew his salary from the crown, leading to impeachment attempts, but the governor refused removal, biasing courts toward British interests over colonial ones.

10. King George III has created numerous new government positions and sent swarms of officials to harass the people and drain their resources.

- After the 1765 Stamp Act, stamp distributors and customs officers flooded colonies with high salaries from colonial funds; by 1768, expanded admiralty courts added more officials, burdensome during Townshend Acts enforcement.

11. King George III has stationed standing armies among us during peacetime without the approval of our legislatures.

- Post-1763 Seven Years’ War, British troops remained in colonies to enforce acts like the Stamp and Townshend, culminating in the 1774 Quartering Act forcing colonists to house soldiers after the Boston Tea Party.

12. King George III has tried to make the military independent of and superior to civilian authority.

- In 1774, General Thomas Gage became Massachusetts governor under the Massachusetts Government Act, merging military and civil power to enforce customs and suppress riots without local approval.

13. King George III has worked with others to impose a foreign legal system on us, one that doesn’t align with our constitution or laws, and has approved their fake legislative acts.

- In 1767, a Board of Trade enforced revenue laws independently via customs commissioners, bypassing colonial legislatures; by 1774, Massachusetts’ council was royally appointed, subjecting colonists to unacknowledged Parliament authority.

14. King George III has forced us to house large groups of armed soldiers among us.

- The 1765 Quartering Act required colonists to shelter British troops, escalating in 1774 when Gage quartered soldiers in Boston homes without consent, punishing the city post-Tea Party.

15. King George III has protected soldiers from punishment for murders they committed against colonists by allowing sham trials.

- In 1768 Annapolis, Maryland, Marines killed two citizens in a dispute but were acquitted despite evidence, seen as a mock trial favoring military over colonial justice.

16. King George III has cut off our trade with the rest of the world.

- The 1774 Boston Port Act closed Boston’s harbor as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, crippling trade and isolating the port city economically until reparations were made.

17. King George III has imposed taxes on us without our consent.

- From 1765’s Stamp Act taxing paper goods to 1767’s Townshend Acts on tea and glass, these levies funded war debts without colonial representation, sparking widespread protests like the Boston Massacre.

18. King George III has, in many cases, denied us the right to a jury trial.

- Post-1768, admiralty courts tried revenue violations without juries, biased toward the crown, as in Boston where customs disputes bypassed local juries under British naval jurisdiction.

19. King George III has allowed colonists to be transported overseas to face trial for alleged crimes.

- The 1774 Administration of Justice Act let governors send accused rioters or officials to Britain or other colonies for trial, like potential cases from Massachusetts tumults, to avoid local juries.

20. King George III has eliminated the free system of English laws in a neighboring province, setting up an arbitrary government there and expanding its borders to serve as a model for imposing absolute rule on the colonies.

- The 1774 Quebec Act extended French civil law and Catholic rights in Quebec, enlarging borders into Midwest territories, seen as a threat to Protestant English common law in adjacent colonies.

21. King George III has revoked our charters, abolished our most important laws, and fundamentally changed the structure of our governments.

- In 1774, the Massachusetts charter was altered to make judges and sheriffs royal appointees, ending jury selection by locals and centralizing power under the governor.

22. King George III has suspended our legislatures and claimed the power to make laws for us in all matters.

- In 1767, New York’s assembly was suspended under the Restraining Act; governors like Virginia’s Lord Dunmore in 1775 issued proclamations as law after dissolving assemblies.

23. King George III has abandoned his role as our government by declaring us outside his protection and waging war against us.

- In early 1775, the king declared colonies in rebellion via Parliament message, followed by the Prohibitory Act blocking trade and hiring Hessians, (German Soldiers) effectively abdicating protection.

24. King George III has attacked our seas, ravaged our coasts, burned our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

- In 1775, Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore seized merchant vessels and ordered naval raids, including burning Norfolk where my 8th Great Grandfather’s land was at Sewell’s Pointe, disrupting coastal communities amid escalating conflict.

25. King George III is currently sending large armies of foreign mercenaries to carry out acts of death, destruction, and tyranny, marked by cruelty and betrayal unmatched even in the most barbaric times, unworthy of a civilized leader.

- By 1776, the king hired Hessian mercenaries from Germany to suppress the rebellion, deploying them in battles like Long Island, notorious for their brutal tactics.

26. King George III has forced our fellow citizens, captured at sea, to fight against their own country, making them kill their friends and family or be killed themselves.

- The December 1775 act authorized capturing American ships and impressing crews into British service, forcing them to fight kin, condemned in Parliament as cruelly savage.

27. King George III has stirred up rebellions within our colonies and encouraged the merciless Native American tribes on our frontiers, whose warfare involves the indiscriminate destruction of people of all ages, genders, and conditions.

- In 1775, Virginia’s Lord Dunmore proclaimed freedom for slaves joining British forces, inciting insurrections; he and others enlisted tribes like Shawnee and Cherokee for frontier attacks.

In the end, these 27 grievances weren’t just complaints—they were the breaking point after years of patient appeals. Time and again, the colonists fought for their rights as full British citizens, petitioning the king and Parliament through documents like the Declaration of Rights and Grievances in 1765 and the Declaration and Resolves in 1774. They begged for representation, fair laws, and equal treatment, offering loyalty in return. But at every turn, they were denied, treated as subjects to exploit rather than citizens to respect. Policies like the uneven citizenship rules in the Plantation Act and royal blocks on naturalization showed how Britain favored control over fairness, shutting doors to immigrants and limiting colonial growth.

This struggle wasn’t just history—it’s the foundation of who we are today. As a direct descendant of George Mason, whose Virginia Declaration of Rights helped shape the path to independence, I see myself as part of this grand journey. And so is every Ethnic American, whether your family arrived centuries ago or 30 years years ago.

We’re all heirs to that fight for freedom, equality, and self-rule. The Declaration of Independence marked the bold step from subjects to citizens of a new nation, reminding us that standing up for our rights is what makes America endure. It’s a legacy we carry forward, ensuring no one is denied their voice in the pursuit of a better tomorrow.

The Grievances as originally written in their 18th century English can be found here

What these grievances mean and parallels in modern times can be found in the addendum to this article here: The Road to Revolution – Addendum: History Rhymes

© James Sewell 2025 – All rights reserved

Pingback:The Road to Revolution – Addendum: History Rhymes - Ethnic American