The Short Legal Definition – Today

An Ethnic American is a white person of good moral character who has lived continuously in the United States for at least five years and can speak English.

That is the 21st-century working definition, built directly on the wording of the Naturalization Act of 1790, adjusted only for the modern residency period (five years is the current naturalization requirement). The rest of the phrase – “free white person… of good moral character” – is lifted verbatim from the first citizenship law ever signed by George Washington.

This is not a slogan. It is a measurable, testable standard. If you meet it, you qualify. If you don’t, you don’t. No feelings, no politics, no debate required. Ethnic American is a white person of good moral character who has lived continuously in the United States for at least two years (1790-1795) or five years (1795- ) and can speak English.

The original 1790 Act required only two years; Congress raised it to five in 1795 and it has remained five ever since (8 U.S.C. § 1427).

That is the 21st-century working definition, built directly on the wording of the Naturalization Act of 1790, adjusted only for the modern residency period (five years is the current naturalization requirement). The rest of the phrase – “free white person… of good moral character” – is lifted verbatim from the first citizenship law ever signed by George Washington.

This is not a slogan. It is a measurable, testable standard. If you meet it, you qualify. If you don’t, you don’t. No feelings, no politics, no debate required.

Where We Came From – The Short Version

Let’s start at the beginning.

Between May 1607 and October 1609, 474 English and other settlers arrived at Jamestown, Virginia. Only 60 souls survived. Of those, 42 were English, 8 Polish, 4 German, 2 Swiss, and 2 French – the first Ethnic Americans. The rest had died to starvation and Powhattan Indian Attacks. 16 or (26%) Were non-English.

Then, in 1620, the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. 72 English and 32 Flemish or Walloon

These were the first Ethnic Americans. A mixed European Ethnicity. My Family arrived in 1610 and 1619.

By 1776, every signer of the Declaration of Independence was of European descent. In fact, every person who voted to ratify the Constitution in the state conventions was a White European man. The official records—called Elliot’s Debates—prove it. No exceptions.

Founding Father John Jay, our First Chief Justice, wrote in Federalist Paper No. 2 that America was made up of “one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion…” He was talking about people of European heritage.

Over time, these different European groups blended. As a result, a new ethnic group was born: Ethnic Americans

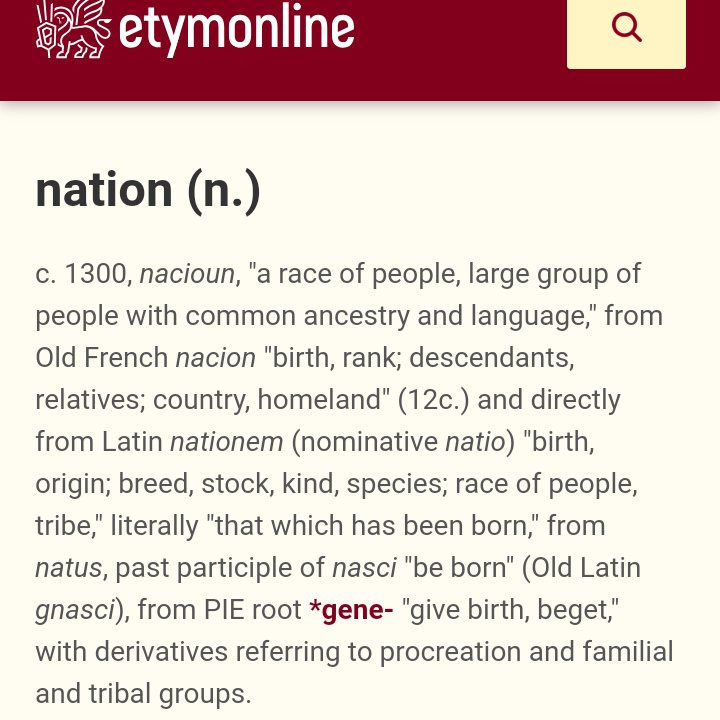

The Etymology of “Nation” – Ethnos, Genos, and the Roots of Our Peoplehood

Before we dive deeper into the laws and numbers, it’s worth pausing on what “nation” – and by extension, “Ethnic American” – actually means at its linguistic core. The word “ethnic” comes straight from the Greek ethnos (έθνος), and understanding it flips the script on how we think about identity today. This isn’t abstract philosophy; it’s the foundation of why the Founders could write “We the People” without blinking – they were describing a specific ethnos, a shared people bound by blood, habit, and custom.

Ethnos (pronounced eth’-nos) literally means “a race (as of the same habit), that is, a tribe, nation, [or] KIN.” It derives from the Ancient Greek verb ἔθω (éthō), which means “that which I am accustomed” – in other words, a group of people who share the same ways, the same ingrained customs, the same lived reality passed down through generations. It’s not just “people in a place”; it’s a collective shaped by what feels natural because it’s yours – your stories, your food, your unspoken rules. In the Bible (where it appears 164 times in the New Testament), ethnos is often translated as “Gentile” or “nation,” but the root sense is always this: a band of folks who stick together because they’re cut from the same cloth.

Tied right to it is genos (γένος, pronounced ghen’-os), the word for “kin” or “stock.” From the verb γίγνομαι (gígnomai, “to be born” or “to become”), genos points to literal descent – your bloodline, your family tree branching out into a clan, tribe, or people. It’s the “of the same family” adjective that underscores everything: a group descended from common ancestors, holding tight to that kinship like a family reunion that never ends. Dictionaries nail it down:

- Kin (noun): A person’s relatives collectively; kinfolk. Or, more broadly, “a group of persons descended from a common ancestor or constituting a people, clan, tribe, or family.”

- Genos (Ancient Greek): “Kin,” “race,” “stock” – the raw material of who you are by birth.

These aren’t interchangeable fluff. Ethnos is the outward habit, the tribe’s rhythm; genos is the inward blood, the unbreakable tie. Together, they form nation – not some border on a map or a passport stamp, but a living web of kin who know each other because they’ve shared the fire for centuries. The Latin natio (birth, tribe) echoes this, feeding into English “nation” as a people of shared origin and custom.

Now, tie this back to our story: The 1790 Naturalization Act wasn’t random bureaucracy. It was the Founders codifying their ethnos – “free white persons” who could slip into the American genos because they already shared the habits (ethnos) and could blend into the kin (genos). Washington, Jefferson, Jay – they weren’t building an idea; they were securing a nation in the ancient sense, a people like the Greeks or Hebrews before them. That 21-month gap? It locked in the ethnos first, rights second. The post-1965 shift? It diluted the genos, turning shared custom into a scramble for scraps.

This etymology isn’t trivia – it’s the why behind the who. We’re not “diverse individuals”; we’re an ethnos of genos-bound kin, fighting to remember our accustomed ways before they’re paved over. If “nation” means tribe by habit and blood, then Ethnic Americans are the tribe that built this one – and the only one told to forget its own name.

The Genetic and Cultural Legacy: A Blended People, Not a Blank Slate

To understand the Ethnic American genos, look beyond the laws to the blood and bones. Genetic studies, like those from 23andMe and AncestryDNA’s 2023 reports on pre-1965 Americans, show a distinct cluster: 60–70% British Isles, 15–20% German/Scandinavian, 10–15% French/Irish/Italian, with traces of Dutch and Huguenot. This isn’t random mixing; it’s generations of intermarriage in colonial stockades, frontier towns, and mill villages, forging a people whose DNA tells a story of shared hardship and triumph.

Culturally, it’s American English – that twangy, Germanic-rooted dialect born from English settlers’ voices mashing with German loanwords and Irish lilt. It’s the King James Bible in every schoolhouse, the fiddle at barn dances, the rifle over the mantel. Elliot’s Debates confirm: Zero non-whites voted on the Constitution, but the “We the People” they ordained was already this blended ethnos, pulling from Europe’s best to build something new. Critics call it “white supremacy.” Facts call it founding reality. Ignoring it doesn’t erase the genes or the ghosts – it just leaves our kids without a map home.

How We Got Here – The Long Version

1607–1788: The Founding Population Takes Root

Jamestown, 1607. Plymouth, 1620. Massachusetts Bay, 1630. New Amsterdam, 1624. Every chartered colony in British North America was settled by Europeans – overwhelmingly English, with smaller numbers of Scots, Irish, Dutch, Germans, Swedes, and French Huguenots. No other continental population contributed to the founding settlements in any meaningful proportion.

By 1776 the colonial population was roughly 2.5 million. Census fragments and parish records show the breakdown:

- 80% British Isles origin

- 10% German / Dutch / Scandinavian

- 6% Huguenot / other Western European

- 4% everything else (mostly indentured servants from the same regions)

Every signer of the Declaration of Independence traced his ancestry to one of those European streams.

Every delegate who voted in the thirteen state ratifying conventions for the Constitution was a white male of European descent.

The published records – Elliot’s Debates, volumes 1–5 – list every name, every vote, every speech.

There is not a single non-European participant recorded.

1789: The First Congress Writes the Rule in Stone

Article I, Section 8 of the brand-new Constitution gives Congress the power and demand “to establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization.”

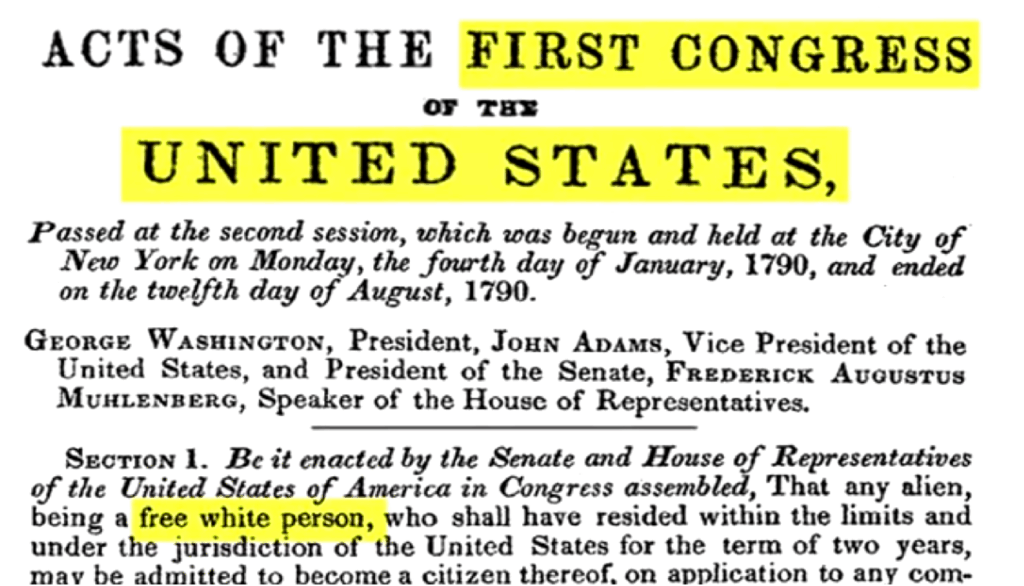

On March 26, 1790 – less than a year after Washington took office – Congress delivered. The Naturalization Act of 1790 is only 350 words long. The key sentence:

“And be it further enacted, That any alien, being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, may be admitted to become a citizen thereof… provided he shall behave as a man of good moral character…”

Two years’ residence. White. Good moral character. That was the entire filter.

March 26, 1790: George Washington signs the Naturalization Act into law. This is the very first citizenship rule from the First Congress. It defines an “American” as a “free white person… of good moral character” after two years’ residence (later bumped to five in 1795).

December 15, 1791: The Bill of Rights (first 10 amendments) is ratified by the states and becomes official.

That’s a 21-month window (exactly 1 year and 9 months).

“Always Remember. 1 year and 9 months lasted between the Act signed into Law by President George Washington (March 26, 1790) and the ratifying of the American Bill of Rights (December 15, 1791). It was established as law BEFORE our Constitutional Rights were even ratified. So, when those rights were enumerated for ‘Americans’ we already had a definition of what an American was. A Free White person of good moral character.”

In short: The people (the citizenry, aka “We the People”) got defined first. The rights (free speech, guns, etc.) got tacked on later. No fluff, no debate—it’s chronological fact from congressional records.

To see the entire timeline of our immigration story in detail please visit my blog post: The Ethnic American Timeline

1790–1920: The System Works Exactly as Designed

The 1790 Act’s two-year residency rule was lengthened to five years in 1795 and has remained five years ever since. The racial restriction stayed in place until 1952. The national-origins quota acts of 1921 and 1924 were explicit: immigration slots were allocated to preserve the ethnic proportions recorded in the 1890 census (the 1890 Census included quadroon and octoroon distinctions as Non-White; that is 12.5-25 admixture).

Tennessee in 1910, Virginia in 1924 introduced the one drop rule.

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act, which reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as “White” a person “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian“

Result by 1960:

- United States population: 88.6% non-Hispanic white

- World population: ~32% white

The policy delivered continuity for 175 years.

1965: The Great Pivot

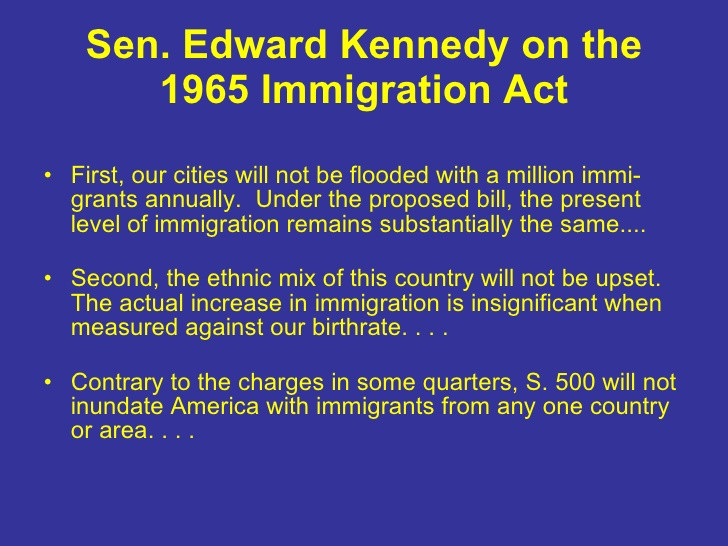

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler) abolished the national-origins system. Sponsors insisted the ethnic balance would remain unchanged. Edward Kennedy, floor manager in the Senate: “The ethnic mix of this country will not be upset… contrary to the charges in some quarters, [the bill] will not inundate America with immigrants from any one country or area…” [see graphic above]

Lyndon Johnson, signing ceremony at the Statue of Liberty:

“This bill is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives…”

Sixty years later:

- United States: ~58% non-Hispanic white

- World: 6–7% white

- Founding stock projected to become a minority by the early 2040s

No peacetime society has ever executed a demographic transformation of this speed and scale.

The Modern Standard – Five Years, White, Good Character, English

The five-year residency rule is still federal law (8 U.S.C. § 1427). “Good moral character” is still the statutory requirement. The racial clause was removed in 1952, but the original wording remains the historical benchmark.

Therefore, the practical 2025 definition of an Ethnic American is:

- White (European ancestry, the same pool the 1790 Act covered)

- Five continuous years of U.S. residence (the current naturalization floor)

- Good moral character (no felony convictions, no habitual drunkenness, no support for totalitarianism – the same 1790 standard)

- Functional English (the 1906 naturalization act added basic English literacy; today it is still required on the citizenship test)

That is it. No blood-quantum debates, no DNA tests, no ideological litmus tests. If you check the boxes, you are in the same legal and historical category as every citizen Washington naturalized in 1791.

Who Meets the Standard Today?

- Old-stock descendants – anyone with family graves in North America before 1900.

- Post-1840 European waves – Irish, Germans, Italians, Poles, Scandinavians who arrived before the 1924 cutoff and whose families have been here five generations or more.

- Recent white immigrants – a German engineer in Texas since 2019, a Polish nurse in Chicago since 2020, an Irish software developer in Seattle since 2018. After five years of continuous residence, good conduct, and passing the English/civics test, they qualify under the modernized 1790 rule.

Common Questions, Straight Answers

Q: Isn’t this just a dressed-up way to say “white people”?” A: Yes – because that is exactly what the 1790 Congress said. The difference is we are quoting them, not inventing the category.

Q: Does the Constitution say America is only for white people ? Yes it does actually if read in context. John Jay our first supreme Court Justice and many of the other founders confirm this. Read the article here to understand how every word in the preamble speaks to our ethnic origins. “We the People” Meant White Only: The Constitution’s Racial Truth

Q: What about the 14th Amendment? A: Ratified in 1868 under military reconstruction. Its citizenship clause was written to cover freed slaves and their children. The same Congress that passed the 14th Amendment also passed legislation barring Asian immigration. They saw no contradiction.

Q: Doesn’t the Statue of Liberty say “give me your tired, your poor…”? A: Emma Lazarus’s poem was added to the pedestal in 1903 – 117 years after the Constitution and 113 years after the 1790 Act. It has zero legal force.

Q: What about Native Americans? A: The 1790 Act did not apply to tribes; they were treated as domestic dependent nations. Tribal citizenship is a separate track and tied to their nations.

Q: What about Black Americans? A: Pre-1965 Black Americans were a small, historically distinct population (about 10% in 1790, 11% in 1960). The 14th Amendment in 1868 gave them birthright citizenship. Their story is American, but it is not the founding story.

Q: Why the English requirement? A: The 1906 Naturalization Act added basic English literacy. Every naturalization ceremony today still requires the applicant to read, write, and speak basic English. It is not new.

Critics’ Objections: Preempting the Attacks

You might hear, “This definition is exclusive or racist.” Fair to question, but let’s look at the record. The 1790 Act wasn’t born of hate – it was pragmatism. John Jay in Federalist No. 2 warned of “foreigners” diluting the “united people” through divided loyalties, echoing Madison’s fears in Federalist No. 43 of immigration overwhelming republican virtue. Elliot’s Debates show the ratifiers debating property qualifications to ensure a stable ethnos, not supremacy.

Today, every nation guards its genos: Japan (98% ethnic Japanese), Israel (Jewish nation-state law), Hungary (Orban’s “Christian democracy”). Only America brands self-preservation as bigotry. We’re not excluding to harm – we’re including to preserve the contract our ancestors signed in blood. Ignore it, and the posterity clause becomes a suicide pact.

Every sovereign nation on earth is expected to protect its historic people. Only one is condemned as immoral for even wanting to.

The Numbers Tell the Story

| Year | U.S. White % | World White % | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | ~80% | ~N/A | First Census |

| 1900 | 87.9% | ~30% | Census / UN estimates |

| 1960 | 88.6% | ~32% | Census |

| 2025 | ~58% | 6–7% | Census projections |

No other developed nation has allowed its founding population to shrink this fast without war or famine.

Practical Implications – 2025 and Beyond

- Cultural continuity – schools, media, and public institutions should reflect the founding population’s history as the default narrative, the same way Japanese schools center Japanese history.

- Immigration policy – a moratorium on non-European immigration until the founding stock stabilizes above 70% would mirror the 1924–1965 pause that preserved continuity for two generations.

- Legal recognition – a formal “Ethnic American Heritage Month” or protected status analogous to Native American tribes would cost nothing and acknowledge reality.

The Bottom Line

The United States was not discovered. It was built brick by brick – by a specific people, under specific laws, for their specific posterity.

Those settlers didn’t just claim land; they tamed wilderness with ax and plow, forged laws from colonial charters into a Constitution that echoed their shared ethnos. The Naturalization Act of 1790 wasn’t a footnote – it was the blueprint, defining citizenship before rights were even enumerated, ensuring the genos of “We the People” stayed true. From Jamestown’s survivors to the quotas that held the line for 175 years, every step guarded the flame our ancestors lit against the dark.

That people still exists. Those laws are still on the books in spirit. That posterity is still having children – in small towns from Appalachia to the Dakotas, in cities where old neighborhoods hold the line, in families tracing roots to the Mayflower or the Famine ships.

But the flame flickers. The post-1965 pivot – that “great replacement” by design or neglect – has scattered our kin, diluted our voice, and turned shared custom into a museum piece. We’ve watched wages stagnate, schools scramble for ESL over shop class, and our kids priced out of the homes our grandparents built. It’s not abstract; it’s the slow erasure of the habits that made us us – the backyard barbecue with stories of great-grandpa at Gettysburg, the church supper where everyone knows the hymn by heart, the quiet pride in a flag sewn from the same cloth as our blood.

An Ethnic American is any white person of good moral character who has lived here five years and speaks English. Not a club for elites, not a relic for historians – a birthright for those who meet the original terms, from 13th-generation Virginians to a fresh-faced Dane who’s paid his dues in sweat and oath.

We are not asking for new rights. We are asking for the original contract to be honored – the one forged in 1787 at Philadelphia, ratified in 1788 by the states, and given teeth in 1790 by Washington’s pen. The one that promised posterity a nation of their fathers’ making, not a boarding house for the world.

Rise up, Ethnic Americans. Claim your ethnos. Reclaim your nation. Before the last brick crumbles, and the house our ancestors built becomes just another tale for strangers to tell.

Written by a 13th-generation Ethnic American. Sources: Founding documents, Federalist Papers, Elliot’s Debates, US Naturalization Acts, Census data, and etymological dictionaries. Additional: Naturalization Act of 1790 (full text), Census historical demographics

Full deep dive at ethnicamerican.org – no spin, just truth.

© James Sewell 2025 – All rights reserved

Pingback:The Ethnic American Library - Ethnic American

Pingback:My Personal Philosophy: Ethno-Originalism - Ethnic American