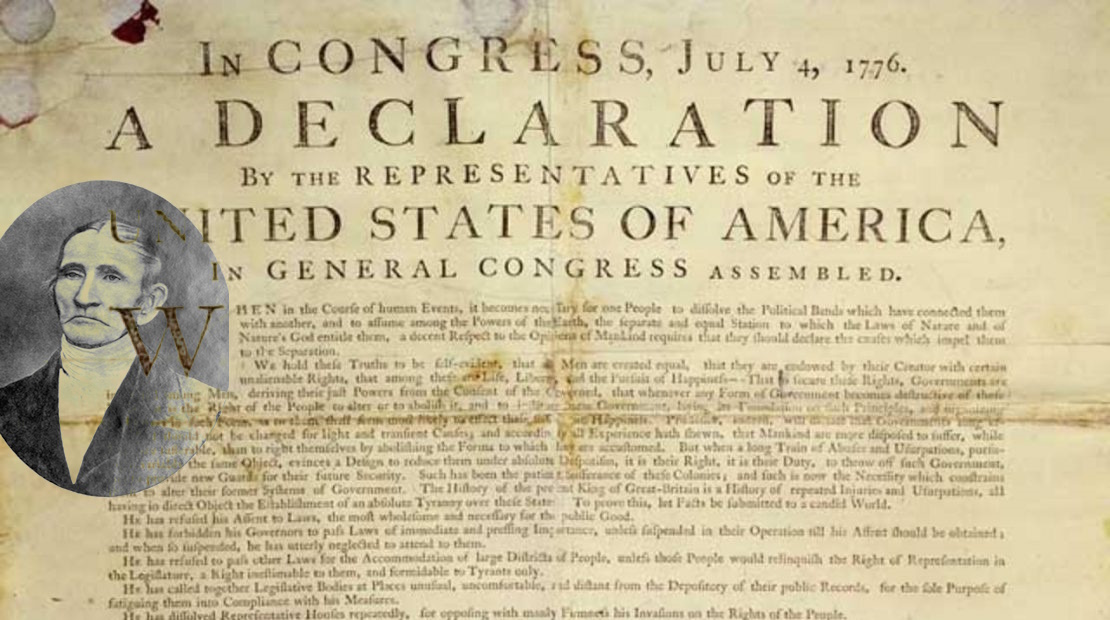

Stephen Pleasonton

The unsung Ethnic American patriot who defied flames and bureaucracy, war and certain capture to safeguard our heritage.

During the War of 1812 Stephan single handily saved the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Articles of Confederation; George Washington’s commission, Final Address, and Revolutionary War correspondence; as well as volumes of treaties, diplomatic dispatches, and state secrets.

Fellow Ethnic Americans, bearers of the unyielding spirit forged in the crucibles of Europe’s ancient lands—English ploughmen, Irish rebels, German blacksmiths, Italian stonemasons, and Polish serfs who braved the Atlantic’s fury to claim this continent—we gather once more to honor the quiet titans among us. Our people, the free white descendants who tilled the soil, erected the cities, and defended the frontiers, have long been the true architects of this republic. Yet, the powers that be—the entrenched elites, the scheming globalists, the revisionist historians—systematically diminish our real heroes. They glorify the aristocrats and generals while consigning the everyday Ethnic Americans, the clerks and keepers who made the profound differences, to obscurity. Today, we exalt one such man: Stephen Pleasonton, a humble accountant of sturdy European stock, born in 1776 in Delaware, whose steadfast courage preserved the very foundations of our nation amid war’s inferno and peacetime’s petty intrigues.

Picture the blistering turmoil of August 1814, during the War of 1812—a conflict that tested the mettle of our young republic against the British Empire’s might. Redcoat invaders, emboldened by victories over Napoleon, descended upon Washington, D.C., their ships slicing through Chesapeake Bay and troops marching relentlessly toward the capital. Chaos reigned: residents fled in dust-choked wagons, government officials scattered. Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. dismissed the threat, sneering that the British “would not come here; what the devil would they do here?” But Stephen Pleasonton, a senior clerk in the State Department under Secretary James Monroe, knew better. Of modest origins—likely tracing back to Irish or English roots, as family lore and records suggest—he was no elite; he was one of us, a diligent Ethnic American embodying the 1790 Naturalization Act‘s vision of free white persons of good character.

When Monroe, scouting on horseback 50 miles southeast, spotted the British advance and sent a urgent note to “take the best care of the Books and papers,” Pleasonton acted with the foresight of our pioneer forebears. Ignoring Secretary of War John Armstrong’s mockery—he retorted that prudence demanded preserving the “valuable papers of the Revolutionary Government”—Pleasonton purchased coarse linen from local merchants and had it sewn into bags of convenient size. With fellow clerks, he packed the nation’s sacred treasures: the Declaration of Independence, with its faded signatures proclaiming our ethnic covenant of liberty; the U.S. Constitution, securing blessings for ourselves and our posterity; the Articles of Confederation; George Washington’s commission and Revolutionary War correspondence, including his Farewell Address; and volumes of treaties, diplomatic dispatches, and state secrets. Securing horse-drawn carts, he crossed the Potomac River bridge, hid the cargo in an abandoned grist mill near a cannon foundry, but Pleasonton, ever vigilant, relocated it overnight upon realizing the site’s peril. Enlisting farmers’ wagons, he hauled the bags 35 miles to Leesburg, Virginia, storing them in an empty house under the sheriff’s key. That very night, as Pleasonton rested in a hotel, the horizon glowed with flames—the British had torched Washington, razing the Capitol, White House, and State Department offices. But our heritage survived, unscathed, thanks to this unsung clerk’s resolve!

Pleasonton’s heroism didn’t end there. Rising through the ranks, he became the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury in 1817, settling accounts for the State Department, Post Office, and the Office of Indian Affairs. In 1820, he assumed oversight of the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment, earning the title of General Superintendent of Lights—a role he held for 32 years until 1852. Starting with just 55 lighthouses and a few buoys, he expanded it to over 300 lighthouses, 42 lightships, and hundreds of aids to navigation. Lacking engineering or maritime expertise, this bookkeeper relied on retired sea captain Winslow Lewis for technical guidance, stubbornly adhering to Lewis’s lamp-and-reflector system for its frugality, even resisting the more efficient but costlier French Fresnel lens. Ship owners, captains, and merchants lodged complaints, leading to congressional inquiries in 1837-38, 1842-43, and finally 1851-52, which faulted lighthouse placement, construction, and illumination. Yet, Pleasonton claimed he saved at least $10 million through his prudent management—echoing the thrift of our Ethnic American ancestors who built empires from pennies.

The powers that be, however, could not abide such independence. In 1852, Congress created the nine-member U.S. Lighthouse Board, summarily ousting Pleasonton. This dismissal devastated him, compounded by his wife Mary’s death the previous year. In a poignant 1853 letter to his friend, Senator James Buchanan—addressed intimately as “Dear Jim”—Pleasonton pleaded for aid in securing a position under President Franklin Pierce. “To be turned out of office now, when I am too old to engage in any other business, with my slender means to live on…would destroy me,” he wrote, underscoring his integrity by recounting how he saved the State Department’s papers, which the British would have paid “many thousands of pounds” to destroy. This pattern of diminishment is the elites’ playbook: sidelining the steadfast Ethnic Americans who perform the grunt work, replacing them with boards and bureaucracies that serve globalist interests over our people’s.

Insights from Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes, a family friend and explorer of the South Seas, Antarctica, and West Coast, paint a fuller portrait. Wilkes described Pleasonton as “an honest and upright a gentleman as ever served the country,” “exact in all his business transactions,” with “much judgment and bonhommie.” Though noting Pleasonton “was not a bright man,” Wilkes praised his “kind hearted” nature and dry humor, adding that he was “intimate with most of the leading men of his day” and often consulted by administrations. Pleasonton’s wife Mary, “accomplished and handsome,” wielded influence through her beauty, wit, and “agreeable and kindly manner.” The couple entertained charmingly, hosting dinners and parties that shaped policies under Presidents Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson. They had six children: two sons and four daughters. Both sons attended West Point; the youngest, Alfred, distinguished himself in the Mexican War and Civil War, commanding the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps at Gettysburg and defeating Confederates in Missouri.

Pleasonton’s story resonates with the heart of Ethnic Americans—our unsung heroes, like the Irish canal diggers, German prairie farmers, Italian railroad builders, and Polish steelworkers, who toiled without fanfare to propel this nation. Men like Matthew Thornton, the Irish-born Declaration signer; Peter Muhlenberg, the German-American pastor-turned-soldier; Filippo Mazzei, the Italian whose ideas inspired Jefferson, and Peter Francisco the 16yr old Portuguese Revolutionary War hero known as “Hercules of the Revolution”, who General George Washington had a personal Broadsword made.

These simple folk, not the silver-spooned, made the difference. Yet, the powers that be erase them through historical erasure, much like the Great Replacement we’ve chronicled: the 1965 Immigration Act’s chain migrations, illegal invasions, and visa abuses that dilute our ethnic primacy, hollow our industries, and steal our birthright. By burying Pleasonton, they obscure our rightful claim—this land built by and for us, the European descendants enshrined in founding laws. I intend to change this and put these men’s names back in the mouths of Ethnic Americans.

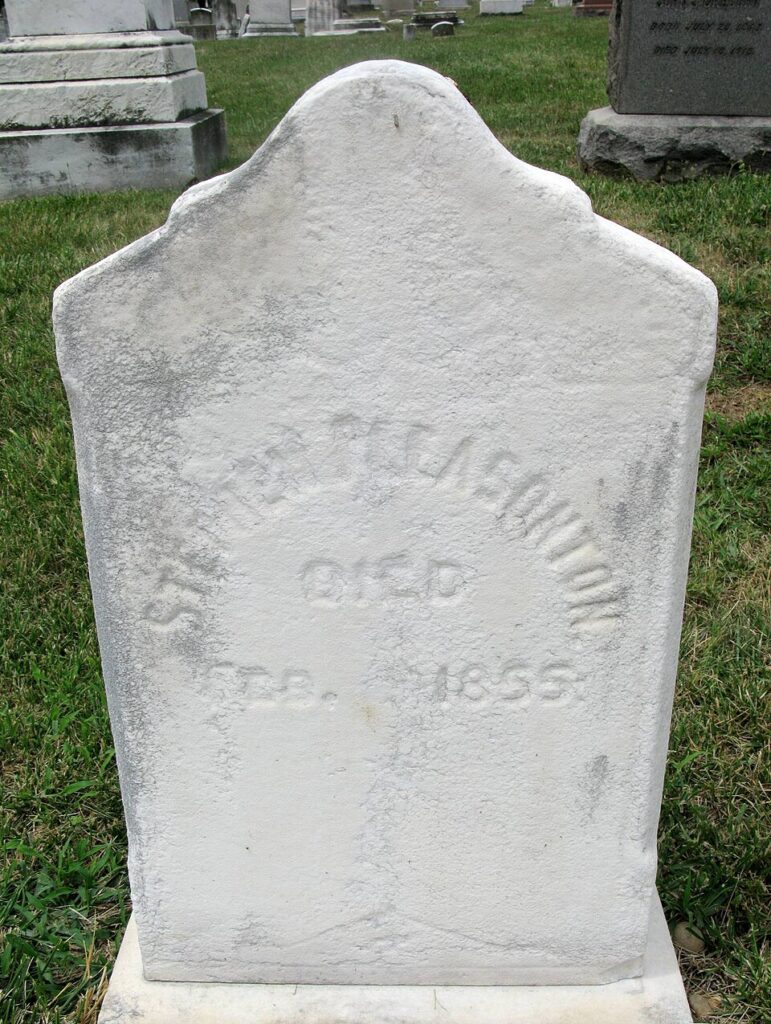

The sadness culminates at his grave in Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C.—Plot Section 2, Range 43, Site 244. Surrounded by senators, congressmen, and notables, this unknown patriot lies in humble repose, his marker unadorned amid the grandeur. Presidents like John Quincy Adams tread nearby paths in life, yet Pleasonton, who preserved the documents enabling their legacies, fades into anonymity.

Visit his grave on Find a Grave and sense the injustice: an unsung hero, locked in obscurity until we, his ethnic kin, revive his tale. Leave your name and a flag or flower. He is one of us, the quiet perseverance amongst a tide of bureaucracy and intrigue. One man, an Ethnic American; like you.

His legacies endure: the Declaration and Constitution, viewed by over a million annually at the National Archives under vigilant guards; lighthouses like Maine’s 1821 Burnt Island Light Station, beacons for immigrants who became part of our fold. In reclaiming Pleasonton, we reclaim our narrative. Fellow descendants of Europe’s valiant voyagers, embrace ethno-originalism, defend our covenant, and let no elite diminish our heroes. For in their quiet valor beats the heart of our people, resilient against the storms of betrayal. Until our next testament to Ethnic American greatness.

© James Sewell 2026 – All rights reserved

A Personal Note from James Sewell:

Dear readers, as I sit here under the Arizona sun on this January day in 2026, reflecting on Stephen Pleasonton’s story, I’m reminded of my own forbearers who crossed oceans and tamed frontiers with nothing but grit and faith. Men like him are the true soul of our ethnic heritage—forgotten by the elites but alive in our hearts. Let’s keep shining a light on these unsung patriots. Stay vigilant, my friends. —James Sewell (@Jamestown_Son)