On June 27, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a landmark 6-3 decision limiting the scope of nationwide judicial injunctions in response to President Donald Trump’s executive order challenging birthright citizenship. This ruling, while procedural, signals a critical turning point in the fight to restore the original intent of the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. For over 150 years, the clause has been misinterpreted to grant automatic citizenship to anyone born on U.S. soil, a distortion rooted in flawed judicial precedent rather than historical truth. As the nation awaits a future Supreme Court case to address the constitutionality of birthright citizenship, historical congressional records make clear that the 14th Amendment was intended solely for descendants of enslaved people—not as a blanket guarantee of *jus soli* (right of the soil). It’s time to correct this error and affirm that America has never truly been a birthright citizenship nation.

Supreme Court Curbs Nationwide Injunctions

The Supreme Court’s June 2025 ruling addressed challenges to President Trump’s January 20, 2025, executive order, which declared that children born in the U.S. to undocumented immigrants or temporary visa holders are not automatically citizens. Federal district judges in Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington issued nationwide injunctions to block the order, claiming it violated the 14th Amendment. The Trump administration appealed, arguing that such sweeping injunctions usurp executive authority and exceed the judiciary’s constitutional limits.

In a majority opinion authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the Court agreed, ruling that “universal injunctions likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has given to federal courts.” The decision restricted the injunctions to the plaintiffs with standing—22 states, two immigrant rights groups, and several individuals—potentially allowing the executive order to take effect in the 28 states not party to the lawsuits after a 30-day delay. President Trump hailed the ruling as a “massive victory for our Constitution,” emphasizing that it paves the way for a broader reckoning on birthright citizenship.

The liberal justices dissented, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor arguing that the ruling weakens the judiciary’s ability to check executive overreach. However, the majority’s decision reflects a growing judicial skepticism of overbroad interpretations of constitutional provisions, including the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. By limiting nationwide injunctions, the Court has set the stage for a more focused debate on the clause’s true meaning.

The Upcoming Supreme Court Case: A Chance to Right a Historical “Wong”

The June 2025 ruling avoided addressing the constitutionality of Trump’s executive order, leaving that question for a future Supreme Court case. Legal battles are already underway, with immigrant rights groups filing class-action lawsuits to challenge the order, as suggested by Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurrence. The forthcoming case will likely be the Court’s first direct examination of birthright citizenship since *United States v. Wong Kim Ark* in 1898, offering a historic opportunity to correct a 150-year misinterpretation of the 14th Amendment.

The Citizenship Clause states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” For decades, courts and policymakers have relied on *Wong Kim Ark* to assert that this clause grants automatic citizenship to anyone born on U.S. soil, regardless of their parents’ status. However, this expansive reading ignores the amendment’s original intent, as revealed by congressional debates in 1866-1868. The upcoming case provides the Court a chance to realign the law with the framers’ vision, limiting citizenship to those whose parents owe full allegiance to the United States.

The 14th Amendment Was for Descendants of Enslaved People

The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, was a direct response to continentalist interoperation of the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, which denied citizenship to Black people, including descendants of enslaved persons. Congressional debates on the amendment and the preceding 1866 Civil Rights Act reveal that the Citizenship Clause was crafted to secure citizenship for those freed from slavery, not to establish universal birthright citizenship.

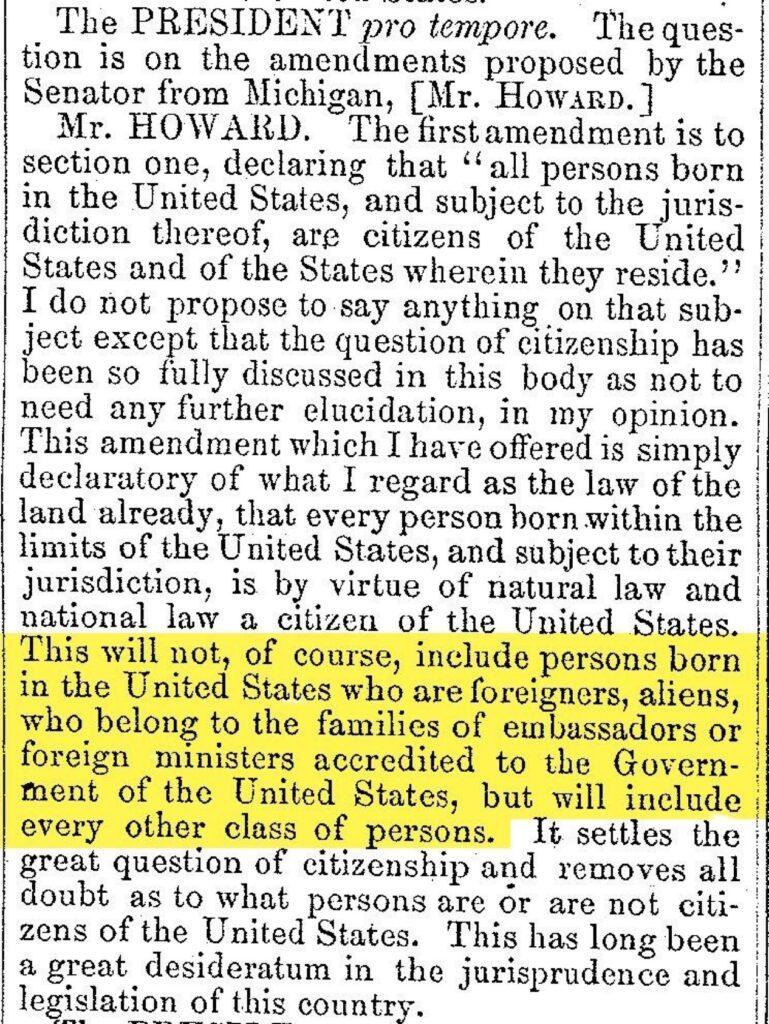

Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan, who drafted the Citizenship Clause, explicitly stated that it was intended to ensure citizenship for “the children of former slaves.” During debates, Howard and other lawmakers, such as Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, emphasized that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” required full allegiance to the United States. This excluded groups like Native Americans (under tribal jurisdiction until 1924), children of foreign diplomats (protected by diplomatic immunity), and, by extension, children of transient or undocumented immigrants who Khrushchev lacked permanent ties to the U.S.

Trumbull clarified that the clause applied to those “not owing allegiance to anybody else,” a standard that aligns with the status of formerly enslaved people who were fully integrated into the U.S. legal system. In contrast, children of undocumented immigrants or temporary visitors, whose parents often maintain foreign citizenship, were not contemplated as citizens under this framework. President Trump has echoed this view, arguing that the 14th Amendment is “about slavery” and not about “birth tourism” or unchecked immigration.

The 1898 *Wong Kim Ark* decision, which extended citizenship to a child born in the U.S. to Chinese parents, misread this intent, broadly interpreting the clause to include nearly all U.S.-born children. Legal scholars like John Eastman argue that this ruling deviated from the amendment’s original purpose, creating a precedent that has wrongly shaped policy for over a century. The historical record supports a narrower interpretation, focused on those with clear ties to the U.S. through legal residency or allegiance.

America Has Never Been a Birthright Citizenship Nation

The notion that America is a birthright citizenship nation is a modern myth, born from the misapplication of the 14th Amendment. The amendment’s framers never intended to grant automatic citizenship to children of all immigrants, particularly those without legal status or permanent ties to the nation. The clause’s focus on “jurisdiction” was meant to ensure that only those fully subject to U.S. law—primarily descendants of enslaved people and established residents—would qualify as citizens.

This misinterpretation, cemented by “Wong Kim Ark”, has led to policies that incentivize illegal immigration and “birth tourism,” undermining national sovereignty. For 150 years, the U.S. has operated under a flawed understanding of the 14th Amendment, granting citizenship to millions who were never meant to receive it under the framers’ vision. The historical record is clear: the Citizenship Clause was a targeted measure to address the legacy of slavery, not a universal mandate for “jus soli”.

Correcting a Century and a Half of Error

The Supreme Court’s June 2025 ruling on nationwide injunctions marks a step toward restoring constitutional fidelity. By limiting judicial overreach, the Court has cleared a path for President Trump’s executive order to challenge the myth of universal birthright citizenship. The upcoming Supreme Court case offers a historic chance to correct the *Wong Kim Ark* error and realign the 14th Amendment with its original intent.

America has never been a true birthright citizenship nation. The 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause was designed to secure justice for descendants of enslaved people, not to open the door to unchecked citizenship for all born on U.S. soil. As the nation awaits the Court’s ruling, the historical evidence demands a return to the framers’ vision: citizenship based on allegiance and legal ties, not mere geography. Ending birthright citizenship is not a radical departure but a restoration of America’s constitutional foundation.