Stop using the term “Heritage American”

Fellow Ethnic Americans—descendants of the European pioneers who forged this republic from wilderness, whether your kin landed at Jamestown in 1610 like mine aboard the Prosperous, or crossed the Atlantic later as free white persons ready to build and defend—we must confront the sly terms creeping into our discourse. As a son of Jamestown settlers, I’ve spent years digging through founding documents, court rulings, and forgotten laws to reclaim our birthright. Through my writings on EthnicAmerican.org, like my series on The Great Ethnic American Displacement, I’ve laid bare how post-1965 policies have eroded the nation our forefathers intended. Today, I turn to “Heritage American,” a phrase bandied about by politicians and pundits. It’s no innocent label—it’s a canard, a weak evasion that fractures our unity by inventing hierarchies among us, distracting from the founders’ clear vision of a nation for free white persons of good moral character.

Defining Ethnic American: The Founders’ Clear Standard

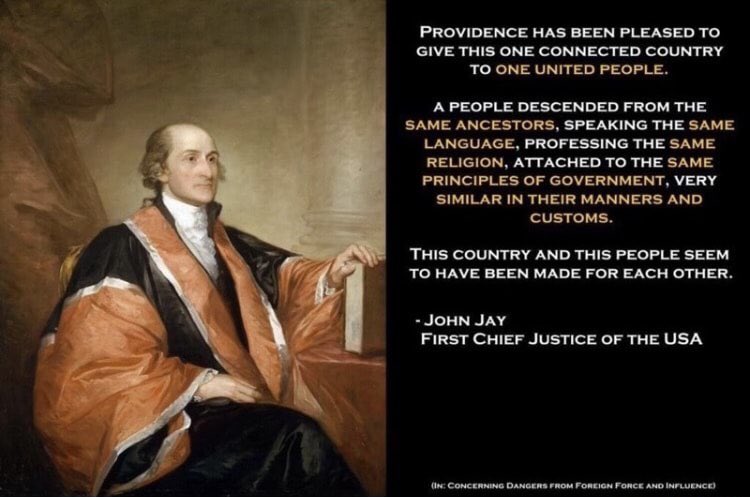

Let’s start with fundamentals. When the founders spoke of “White” in their laws and writings, they meant persons of pure European descent—those from the British Isles, Germany, France, Scandinavia, and kindred stocks who shared a common European heritage, language roots, and cultural mores. This wasn’t vague sentiment; it was precise. As John Jay articulated in Federalist No. 2, “We the People” referred to a united folk “descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs.” This original intent for the Preamble’s “We the People… to secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity” envisioned a homogeneous European posterity, as I explain in detail in my article “The U.S. Constitution Was Only for White People“.

To hammer this home, the founders codified it just months later in the Naturalization Act of 1790, restricting citizenship to “free white persons” of “good moral character.” As I detail in my article “What is an Ethnic American?“, this is the bedrock definition: a white person of good moral character who has resided in the United States for at least five years and can speak English.

It’s not about diluted modern categories that lump in mixed ancestries or MENA peoples under “white.” No—the founders envisioned a homogeneous people. This purity of intent shines through Elliot’s Debates, the compiled records of the Constitutional ratification conventions. In Virginia’s debates, for instance, delegates like Patrick Henry and James Madison emphasized a republic for a cohesive people, wary of foreign influences that could fragment society. Americans, per the founders, can only be Ethnic Americans: those meeting this European-descended, character-based criterion. No tiers, no subclasses—just equals under the law they crafted.

The Constitutional Mandate: How Positive Law Demanded the 1790 Act

Positive law (Latin: ius positum) are human-made law that oblige or specify an action.

Positive law also describes the establishment of specific rights for an individual or group.

Etymologically, the name derives from the verb to posit.The founders didn’t craft the Naturalization Act on a whim; the Constitution compelled it as positive law. Article I, Section 8, Clause 4 grants Congress the power “To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization.” This wasn’t optional—it was a directive to create a nationwide standard, replacing the patchwork of state rules that existed under the Articles of Confederation. The First Congress, convening its session on January 4, 1790, in New York City, wasted no time, beginning debate on the bill by February 3, 1790—just one month into the session. The House passed it on March 4, the Senate on March 19 with amendments, and after quick reconciliation, President George Washington signed it into law on March 26, 1790. This rapid action—finalized within three months of the session’s start—underscores how vital it was to define who could join “We the People” and preserve the republic’s ethnic and cultural integrity.

Critically, this all happened well before the Bill of Rights was even ratified on December 15, 1791—over a year and nine months earlier. The founders prioritized safeguarding the nation’s demographic foundation above even enumerating individual liberties, knowing that without a unified people, those rights would crumble!

Without this uniform rule, the young nation risked dissolution through unchecked influxes that could overwhelm its European core. As debates in Elliot’s collection reveal, framers like Madison feared “the admission of foreigners into the administration of our national government” without safeguards. The 1790 Act, and refinements in 1795 and 1798 extending residency to five years, fulfilled this mandate, ensuring only those who could assimilate—free white persons of good character—became citizens.

The Canard of “Heritage American”: Invented Division

Now, to “Heritage American.” This term, rippling through right-wing circles, purports to honor those tracing roots to the founding era—often implying Anglo-Protestant “old stock.” But search the founders’ words: you’ll find no such distinction. They welcomed all free white Europeans who met the criteria, without demanding Mayflower pedigrees.

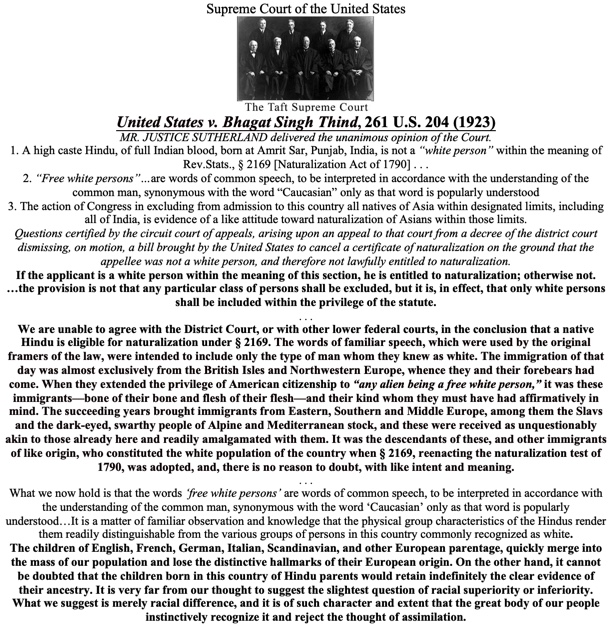

As the Supreme Court affirmed in 1923’s United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind case, “White” encompassed Caucasian Europeans broadly, not just early colonists. All base on Rev, Stats § 2169. The Naturalization Act of 1790

Today the words, “Heritage American” creates artificial rifts, suggesting superiority for those with 18th-century ties over later arrivals like 19th-century Irish or Germans—who were fully Ethnic Americans once naturalized.

This isn’t accident; it’s division. On the left, it lets critics paint our restoration calls as absurd gatekeeping. On the right, many politicians wield it as a softened proxy for “Ethnic American,” too timid to quote the founders directly. If our ancestors mustered the grit to defy the British Empire—the mightiest ever—we expect no less from leaders. Anything milder is cowardly evasion, dodging the founders’ blunt language to appease modern sensitivities.

Politicians’ Timid Dance with the Term

Scan the web and X, and you’ll see “Heritage American” invoked by figures like JD Vance and Vivek Ramaswamy. Vance, in a July 2025 Claremont Institute speech, alluded to cultural continuity tied to early Americans, framing it as “heritage” without embracing the founders’ racial clarity. Ramaswamy, at Turning Point USA in December 2025, dismissed fixation on “heritage” as “loony,” pushing merit instead—yet both skirt the 1790 Act’s explicit terms. Popularized by voices like Jay Engel, who calls himself a “Heritage American,” it echoes nativist undertones but dilutes our unified claim. Why not stand firm? As I argue in “The Great Ethnic American Displacement Part XVI: Reclaiming the Republic“, we need bold restoration of pre-Hart-Celler policies, not watered-down labels.

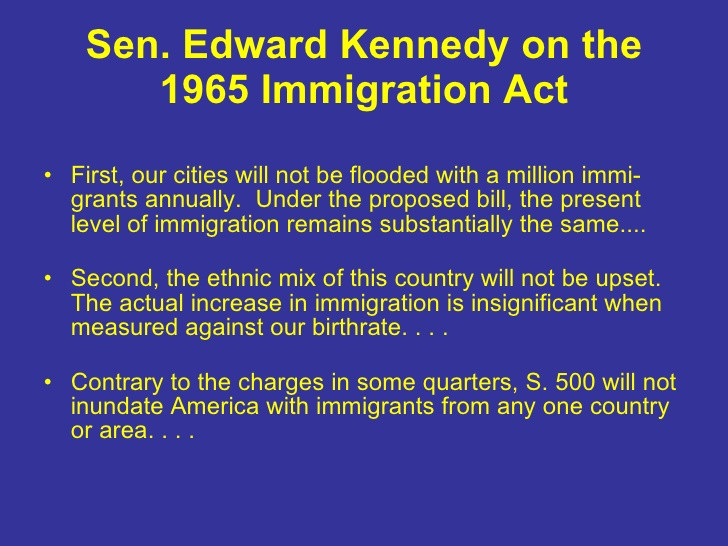

The 1965 Hart-Celler Act, sponsored by Edward Kennedy with false assurances of unchanged demographics, shattered this. Kennedy vowed no floods of immigrants, no ethnic upheaval—lies that enabled the displacement I chronicle in my article, “The Ethnic American Timeline“

Ethnic American vs. Heritage American: A Clear Contrast

To illustrate the fallacy, consider this table:

| Aspect | Ethnic American | Heritage American |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Free white person of pure European descent, good moral character, residing 5+ years in U.S., per 1790-1798 Acts. | Often limited to descendants of pre-Revolution or early colonial settlers, implying Anglo-Protestant priority. |

| Founders’ Basis | Explicit in Federalist Papers, Constitution, and Naturalization Acts—open to all qualifying Europeans. | No founding document support; modern invention creating unnecessary hierarchies. |

| Rights and Equality | Full citizenship and equality upon naturalization; no tiers among whites. | Suggests superior status for “old stock,” dividing whites into “true” heirs vs. later arrivals. |

| Purpose in Discourse | Unites all qualifying Americans of European Descent under the Founders’ vision. | Divides whites, weakening calls to restore pre-1965 America. |

Real Examples: Equality Without “Heritage”

The founders’ framework levels us all—no need for “heritage” badges. Here are cases:

- A 22-year-old from Oslo, Norway—pure European descent, good character, in America 5 years: Full Ethnic American, with every right my Jamestown forebears held.

- An Italian immigrant’s grandson, arrived 1890, naturalized after residency: Ethnic American equal to any, per the Acts—no “heritage” required.

- A German farmer’s descendant from 1848 upheavals: As American as Washington’s kin, bound by shared blood and loyalty.

These aren’t lesser; they’re us. The Constitution, Federalist No. 2, and Elliot’s Debates confirm: unity in European heritage, not generational scorekeeping.

Reclaiming Our Founders’ Nation

As an Ethnic American of founding stock, with roots tracing back to 1610 Jamestown, I refuse to let “Heritage American” splinter us further. I’ve poured my life into exposing these distortions—through articles like my deep dives on ethnicAmerican.org/author/james/—because I see my ancestors’ blood in this soil, and I won’t watch it washed away by timid rhetoric or divisive labels.

We Ethnic Americans must demand more from our leaders: the courage to invoke John Jay, George Washington, and the 1790 Act outright. No proxies, no cowardice. Our forefathers built a nation for us—their posterity of pure European descent—and it’s our duty to reclaim it intact. Anything less betrays their sacrifice. The future of our people hinges on this unity; let’s stand firm, as they did, and restore the republic they envisioned. No more, no less.

© James Sewell 2025 – All rights reserved

Pingback:The Ethnic American Library - Ethnic American

Excellent article!

Pingback:Ye’ Grande Ole Ethnic American Cliff Notes - Ethnic American