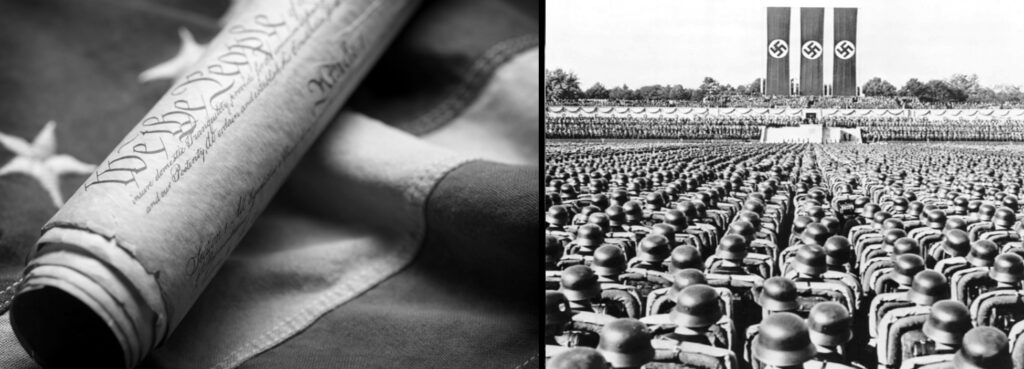

Why I Choose Constitutionalism over National Socialism

As a lifelong advocate for Ethnic American Constitutionalism, I have always stood firmly with the principles that built this nation for our people—the free white persons of good character who swore allegiance to the Constitution, as outlined in the Naturalization Act of 1790. I have never wavered from that commitment. However, I fully recognize the powerful allure that National Socialism holds for many young men today who feel the weight of cultural displacement and seek a path to reclaim our heritage. The disciplined aesthetics of the movement, the sense of unyielding purpose in its imagery, and the promise of decisive action against perceived enemies—these elements resonate deeply in a time when our republic seems adrift. It is not my place to judge those drawn to it; many are sincere patriots searching for strength in the face of erosion. My goal here is simply to share why I believe our own founding framework offers a superior foundation—one rooted in our ethnic American identity, proven by history, and capable of enduring without the pitfalls that have doomed other paths. Let us discuss this as men of shared ancestry, examining the evidence together with respect for all viewpoints.

Addressing a Common Objection: History’s So-Called Inevitability of the Strongman

A frequent argument from those sympathetic to National Socialism is that no significant change in government has ever occurred without a dominant leader—a strongman, or Führer figure—to impose it. Examples cited often include ancient conquerors like Alexander the Great or Genghis Khan, or modern figures such as Napoleon, Stalin, or Hitler himself. This narrative suggests that bold transformation demands an iron-willed individual to cut through inertia and opposition. I respect the weight of these historical examples; they illustrate moments of rapid upheaval. Yet, upon closer examination, history reveals numerous instances of profound governmental shifts that occurred without reliance on a single authoritarian figure. These changes were driven by collective action, institutional evolution, or decentralized movements—often involving armed struggle or negotiation, but not centered on one infallible leader.

Below are key historical examples, drawn from verifiable records, demonstrating how distributed power structures have effected large-scale transformation:

Circa 2334 BCE: Transition from Sumerian City-States to the Akkadian Empire

Description of the Change: In ancient Mesopotamia, the Sumerian civilization—known for innovations like writing and urban planning—evolved into the Akkadian Empire through a combination of military campaigns, diplomatic alliances, and administrative reforms led by Sargon of Akkad. While Sargon was a formidable military leader, the transition was not the product of his unilateral will alone; it involved coalitions among multiple city-states, shared cultural adaptations, and bureaucratic innovations that persisted beyond any one individual.

Key Insight: This early example shows how federated structures and mutual agreements among elites and commoners can unify vast territories without absolute personal dictatorship, laying groundwork for later legal systems like our own constitutional federalism.

508 BCE: Establishment of Athenian Democracy

Description of the Change: Following the overthrow of the tyrant Hippias, Cleisthenes proposed reforms that reorganized Athenian society into tribes and demes, creating a system of citizen assemblies and ostracism votes. This was ratified through popular deliberation in the ecclesia, not imposed by a solitary ruler.

Key Insight: The result was a participatory government for tens of thousands, influencing Western political thought—including our Founders—without a central Führer enforcing compliance.

1215 CE: Signing of the Magna Carta in England

Description of the Change: English barons, facing King John’s arbitrary rule, compelled him to seal the charter at Runnymede through a show of unified force and negotiation. It limited royal power, introduced due process, and sowed seeds for parliamentary authority, evolving over centuries without a revolutionary strongman.

Key Insight: This foundational limit on executive power spread across Europe and directly informed the English common law tradition that shaped American constitutionalism.

1688 CE: Glorious Revolution in England

Description of the Change: Parliament, dissatisfied with King James II’s absolutist policies and Catholic leanings, invited William of Orange and Mary Stuart to invade and assume the throne. The transition occurred with minimal bloodshed—James fled without major resistance—and resulted in the Bill of Rights 1689, which enshrined parliamentary supremacy and habeas corpus.

Key Insight: A bloodless shift from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy, driven by elite consensus and public support, without a dictatorial conqueror imposing change.

1776–1789 CE: The American Revolution and Ratification of the U.S. Constitution

Description of the Change: Thirteen colonies coordinated a war of independence through committees of correspondence and continental congresses, culminating in a constitutional convention where delegates debated and compromised on a federal system. General Washington led militarily but deferred to civilian authority, rejecting monarchical overtures.

Key Insight: A revolution spanning millions, won and structured by collective resolve and written safeguards, not one man’s decree—directly our heritage.

1848 CE: The Revolutions Across Europe (Springtime of Nations)

Description of the Change: From the French Second Republic to uprisings in the German and Italian states, demands for constitutional governments and national unification spread through assemblies, petitions, and provisional committees. In Denmark, for instance, a constituent assembly drafted a liberal constitution amid widespread public support.

Key Insight: Multiple regimes reformed or fell across the continent through coordinated civic action, not isolated dictators, paving the way for modern nation-states.

1987–1991 CE: The Singing Revolution in the Baltic States

Description of the Change: In Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—then Soviet republics—massive nonviolent demonstrations, folk song festivals, and human chains (like the 1991 Baltic Way linking 600,000 people across 370 miles) pressured Moscow to grant independence. Cultural organizations and local parliaments coordinated the effort, leading to declarations of sovereignty in 1990–1991.

Key Insight: Three nations totaling 8 million people broke free from a superpower through grassroots cultural resistance and diplomatic maneuvering, without a singular revolutionary strongman.

1989–1991 CE: The Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe and Dissolution of the Soviet Union

Description of the Change: What is often simplified as “the Fall of the Berlin Wall” was actually a cascade of individual transitions: Poland’s Solidarity movement negotiated the Round Table Agreement in 1989, leading to semi-free elections; Hungary opened its borders in May 1989, sparking refugee flows; Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution saw student-led protests topple the regime in November without violence; Romania’s violent uprising in December ousted Ceaușescu but transitioned via ad hoc councils. By 1991, Soviet republics declared independence through referendums and accords like Belavezha, dissolving the USSR.

Key Insight: Over a dozen nations shed communist rule—collectively affecting 300 million people—through localized protests, negotiations, and votes, not a unified strongman coup; each country’s shift was autonomous, amplifying the collective impact.

These cases span millennia and continents, showing that transformation—violent or otherwise—frequently arises from distributed agency. Even in the Akkadian example, Sargon’s role, while central, depended on alliances that distributed power, preventing the total collapse that often follows a strongman’s death. Strongmen like Alexander or Stalin may accelerate change, but their legacies fracture: Alexander’s realm divided among generals, Genghis Khan’s empire splintered into warring khanates. In contrast, constitutional mechanisms like those in our founding documents foster resilience, allowing our ethnic American people to adapt and thrive. National Socialism, by comparison, endured for only twelve years (1933–1945) before total defeat; our republic has lasted 248 years, and precedents like England’s constitutional monarchy (post-1688) or Denmark’s (post-1849) have persisted over 300 and 175 years, respectively, enabling rectification through amendments and elections rather than revolutionary purges.

The Superiority of Our Founding Principles to the Führerprinzip

National Socialism places the Führerprinzip—the Leader Principle—at its core, requiring absolute obedience to a singular authority. This is not a peripheral element but the ideological foundation, as Adolf Hitler explicitly stated in Mein Kampf (Volume 2, Chapter 4, “The State”): “The Führerprinzip [expresses] the basic principle that the authority of an individual leader is absolute and not subject to any kind of control.” He further elaborated that it demands “unconditional obedience” and subordinates all individual freedoms to the party’s collective will, leaving “no longer any free realms in which the individual belongs to himself.” These words, from the 1925–1926 edition (James Murphy translation, verifiable in archival editions), underscore that the principle is non-negotiable for the movement’s structure.

In contrast, Ethnic American Constitutionalism rejects such concentration of power, drawing instead from the profound insights of the Federalist Papers, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke and Montesquieu. These documents were crafted because the Founders understood human nature’s flaws. James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 51: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” This philosophy of checks and balances—separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches—ensures no single leader becomes unchecked.

The Declaration of Independence empowers “We the People”—our ethnic forebears—to “alter or abolish” any destructive government, a right rooted in Locke’s natural rights to life, liberty, and property. George Washington exemplified this rejection of absolutism during the Newburgh Conspiracy of March 1783. With the Continental Army encamped at Newburgh, New York, unpaid officers—frustrated by Congress’s inaction on back pay and pensions—plotted a coup to march on Philadelphia and install Washington as a king-like figure, effectively ending the republican experiment. Washington, learning of the scheme, convened the officers and delivered a stirring address. To underscore his commitment to civilian authority, he removed his spectacles to read a letter from Congress, pausing to say, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I find that I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.” This humble gesture, coupled with his condemnation of the plot as a betrayal of the Revolution’s ideals, quelled the mutiny without force. Shortly thereafter, on December 23, 1783, Washington appeared before Congress in Annapolis, threw down his epaulets (the shoulder insignia of his rank), and formally surrendered his commission and sword, declaring, “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theater of action.” By refusing the mantle of monarch—despite the army’s readiness to crown him—he preserved the fragile republic, setting a precedent against the very god-king model Hitler later prescribed.

Montesquieu’s influence further fortified this structure. In his seminal work, The Spirit of the Laws (1748), Montesquieu argued that liberty requires dividing government into three independent branches—legislative (to make laws), executive (to enforce them), and judicial (to interpret them)—each checking the others to prevent any one from accumulating tyrannical power. The Founders directly adopted this in Articles I, II, and III of the Constitution, ensuring, for instance, that the president could veto laws but Congress could override, or that courts could declare actions unconstitutional. This tripartite design directly counters the Führerprinzip’s unchecked executive, which Hitler described as immune to “any kind of control,” by institutionalizing rivalry among branches to safeguard the people’s sovereignty.

Even Hitler acknowledged this incompatibility in his Table Talk (entry for May 12, 1942, from the Trevor-Roper edition): “The American is a born rebel against authority… I don’t see how National Socialism could ever take root there.” These sources—Mein Kampf and Table Talk—are drawn directly from National Socialist-era publications, available in neutral historical repositories.

Our system prioritizes merit-based assimilation for free white persons, as per the 1790 Act, fostering a unified ethnic identity through oath-bound loyalty to the republic, not a person. It builds strength through guarded liberty, not submission.

The Perils of Succession: From Hitler to Hermann Göring

One critical vulnerability in a system dependent on the Führerprinzip is succession. Without institutional safeguards, the movement hinges on one man’s vitality, and his replacement may betray the very ideals he championed. Hitler designated Hermann Göring as his successor in 1934, following President Hindenburg’s death, making Göring the second-highest figure in the Nazi hierarchy until 1945. Göring’s actions, however, exemplified self-enrichment over racial or national loyalty, undermining any claim to selfless leadership.

Göring, as Reichsmarschall and head of the Luftwaffe, orchestrated widespread looting during the war. Through the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg—a special task force for cultural plunder—he acquired over 4,000 artworks, including masterpieces by Rembrandt (such as “Portrait of a Young Woman,” valued at approximately $30 million today), Jan van Eyck panels, and Lucas Cranach altar pieces (each exceeding $20 million in modern estimates). These were seized from not only Jewish collections but, French museums, and private European owners, often in exchange for concentration camp labor that produced crates of contraband shipped to his estate. His Paris agent, Bruno Lohse, meticulously cataloged thousands of items at the Jeu de Paume depot. The proceeds funded Göring’s lavish hunting expeditions in the Bavarian forests and his personal drug habits. Meanwhile, as Allied bombs devastated Berlin in 1943–1945, reducing much of the city to rubble, Göring prioritized expanding his Carinhall residence—a sprawling palace filled with stolen tapestries, sculptures, and furniture worth hundreds of millions.

Such conduct directly contradicts the 14 Words—”We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children,” coined by David Lane in the 1980s as a call to ethnic preservation. Göring’s plunder enriched himself at the expense of European cultural heritage, including that of fellow white nations like France and the Netherlands, offering no security for future generations. In a Constitutional republic, term limits, elections, and oaths to the document—not a person—prevent such devolution. We guard against tyrants and their heirs through vigilant institutions, ensuring continuity for our posterity.

David Lane’s 88 Precepts: A Respectful Examination of Intent and Outcome

David Lane was a courageous and dedicated activist whose writings, born from personal sacrifice in the fight for white identity, have profoundly inspired many seeking to defend their heritage. His 88 Precepts, composed during his imprisonment in the 1990s, offer a series of principled statements aimed at guiding racial preservation and societal renewal. Principles such as the fourteenth—”In accord with Nature’s Laws, nothing is more right than the preservation of one’s own race”—and the twenty-ninth—”The concept of ‘equality’… is declared a lie by every evidence of Nature”—resonate as calls to recognize biological and cultural realities. The choice of eighty-eight statements, evoking “Heil Hitler” through numerology, adds a layer of symbolic defiance.

Yet, when evaluating these precepts against historical application, it is worth considering their implementation through groups like The Order, which Lane helped form. The organization’s actions, intended to fund and advance white nationalist goals, included armed robberies and the 1984 assassination of Denver radio host Alan Berg. Berg, a Jewish broadcaster known for provocative commentary, was killed in a car bombing outside his home. While the intent was to strike against perceived anti-white rhetoric, the result was not the broader liberation envisioned. Instead, it prompted intense federal investigations, leading to the arrest and life imprisonment of several members, including Lane himself. David Lane spent his final years in a supermaximum-security prison, where his influence continued through correspondence but did not translate into widespread societal change. This outcome, though tragic for a man of such conviction, highlights the challenges of translating abstract principles into effective action without broader institutional support.

In comparison, our founding documents—the Federalist Papers, Constitution, and Bill of Rights—provide a far more comprehensive blueprint. The Federalist Papers consist of eighty-five detailed essays by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay, systematically analyzing federalism’s mechanics: how to balance state and national powers, mitigate factions, and implement checks against abuse. The Constitution itself, at roughly 4,500 words, delineates precise structures—three co-equal branches, enumerated powers, and an amendment process for adaptation. The Bill of Rights secures ten fundamental protections, from free speech to bearing arms, grounded in Enlightenment reason from Locke (natural rights) to Montesquieu (power separation). These texts scaled a diverse continent into a unified republic, fostering innovation and defense for our ethnic forebears. Lane’s precepts, while eloquent and motivational, form a more concise list of axioms—approximately 5,000 words total—focusing on philosophical imperatives but lacking granular guidance on governance. The twenty-second through thirty-second precepts, for instance, emphasize racial purity through historical analogies, but do not detail administrative frameworks. This depth in our documents has sustained a nation; the precepts, noble as they are, have fueled passion more than policy.

The Industrialist Bargain and Hitler’s Pattern of Betrayal

The rise of National Socialism was not solely a grassroots triumph but involved strategic alliances with Germany’s industrial elite, who provided crucial financial support in exchange for assurances against radical reforms—specifically, the dismantling of the Sturmabteilung (SA) if Hitler sought their backing. On February 20, 1933, at Hermann Göring’s official residence in Berlin, Adolf Hitler met with approximately twenty-four leading businessmen, including Gustav Krupp of the steel conglomerate, executives from IG Farben (the chemical giant), Friedrich Flick of the steel and coal empire, and Günther Quandt of the arms and battery firms. Hitler outlined his vision: the end of parliamentary democracy in favor of a strong authoritarian state that would protect private enterprise from socialist threats. Göring explicitly solicited “financial sacrifices” to fund the upcoming March 5, 1933, elections, proposing three million Reichsmarks (equivalent to about twenty million dollars today). Contributions poured in immediately: IG Farben donated 400,000 Reichsmarks, the Ruhr coal and iron association another 400,000, and Deutsche Bank 200,000. This infusion cleared the Nazi Party’s twelve-million-Reichsmark debt and financed propaganda and paramilitary operations, securing a coalition victory with 43.9 percent of the vote.

The explicit quid pro quo emerged soon after: The industrialists and military leaders demanded the curbing of the SA’s “second revolution” ambitions—land reforms and nationalizations that threatened their holdings. Hitler agreed, fabricating a narrative of an imminent “Röhm Putsch” (coup) and unleashing the purge on June 30–July 2, 1934. Ernst Röhm’s SA had been indispensable to Hitler’s ascent; without Röhm, Hitler might have remained an obscure agitator ranting in Munich beer halls. Röhm, a World War I veteran and Hitler’s closest early ally, founded the SA in 1921 as a modest bodyguard unit of a few dozen men to shield Nazi meetings from communist thugs. Over the grueling 1920s—marked by economic hyperinflation, failed putsch attempts, and street warfare—Röhm expanded it into a paramilitary juggernaut of four million by 1934. He personally recruited from veterans’ halls, endured arrests alongside Hitler after the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, and commanded the Brownshirts to intimidate rivals, shatter strikes, and rig the 1933 vote through voter harassment and ballot stuffing. Röhm’s tireless loyalty transformed the Nazis from fringe fanatics into a mass movement capable of seizing power.

Yet Hitler chose the industrialists’ money and assurances over the lives of these devoted comrades—his own people, bound by blood and battle. Over 85 to 200 individuals were executed without trial, including Röhm (shot while imprisoned in his pajamas at Stadelheim Prison), Gregor Strasser (shot in Gestapo custody after organizing early party cells in the 1920s), and former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher (gunned down in his home alongside his wife). A retroactive law, the “Law Regarding Measures of State Self-Defense,” legalized the massacre. This purge secured elite loyalty: the army swore personal oaths to Hitler, and firms like Krupp and IG Farben profited immensely from rearmament contracts. Such a betrayal—trading loyal white Germans for corporate coffers—stands in stark opposition to the 14 Words’ call to secure our people’s future.

This event reveals a pattern in Hitler’s approach: He consistently used allies for advancement, then discarded them when they outlived their utility. Dietrich Eckart, Hitler’s early mentor and a key intellectual influence, contributed significantly to the writing and editing of Mein Kampf—introducing anti-Semitic themes and refining its propaganda style—before his death in 1923, after which Hitler dedicated Volume 2 to him but moved on without further acknowledgment. The Strasser brothers, Gregor and Otto, built the party’s organizational cells in the early 1920s, drawing in working-class support, only to be purged or exiled for their socialist-leaning views. Even General Erich Ludendorff, Hitler’s co-conspirator in the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch that launched his national profile, was sidelined post-prison, reduced to a marginal figure. These betrayals were not aberrations but necessities of the Führerprinzip, where loyalty to the leader supersedes all.

Hitler’s Personal Dependencies: A Closer Look at His Health

Further complicating the image of unyielding leadership is Hitler’s reliance on drugs, administered by his personal physician, Theodor Morell. Morell’s detailed medical logs, preserved in German archives, and reports from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the precursor to the CIA, America’s wartime intelligence agency) document a regimen that began in earnest during World War II. From 1941 onward, as the Eastern Front stalled, Morell provided hourly cocaine eye drops and lozenges for sinus issues, methamphetamine injections (branded Pervitin) to combat fatigue, and opiate-based Eukodal for gastrointestinal pain. By 1944, Hitler received up to eighty injections in a single month, including combinations that induced manic “blitz” episodes—intense, drug-fueled highs that sharpened focus temporarily but clouded judgment over time.

These issues traced back earlier: Hitler suffered from tremors resembling early Parkinson’s disease since his youth in the 1910s, possibly exacerbated by stress or genetics; in the 1920s, he battled chronic irritable bowel syndrome, leading to digestive crises that Morell treated with increasingly potent substances. This dependency warped key decisions, such as the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, launched amid amphetamine-induced overconfidence. While no man is infallible, such vulnerabilities underscore the risks of vesting absolute power in one individual, absent the redundancies of a constitutional system.

No Successful Precedent for National Socialism

Claims that nations like Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal, or even Finland achieved lasting success under National Socialist principles do not hold under scrutiny. Sweden maintained a social democratic welfare state during and after World War II, emphasizing neutrality and universal benefits without racial hierarchies or a Führer cult—it traded with all sides but never adopted NS ideology. Switzerland’s confederate neutrality, codified in 1815, relies on armed citizen militias and cantonal autonomy, mirroring federalism more than fascism; it hosted Nazi gold but rejected the doctrine outright. Portugal under António de Oliveira Salazar operated a corporatist Estado Novo from 1933 to 1974, blending authoritarianism with Catholic traditionalism in a small, 95 percent ethnically homogeneous population of ten million. Even this endured only through repression and ended peacefully in the 1974 Carnation Revolution, where soldiers and civilians overthrew it with flowers in rifle barrels.

Some point to Finland as an example of National Socialism “working,” citing its wartime alliance with Germany or fringe groups in the 1930s. This is a misunderstanding. Finland never adopted National Socialism as state policy. In the 1930s, the short-lived Lapua Movement (1929–1932) was a right-wing anti-communist paramilitary that admired aspects of Italian fascism but collapsed due to internal divisions and government suppression—no Führer cult or racial laws emerged. Tiny explicit NS groups, like the Finnish National Socialist Community (active 1933–1944), peaked at around 1,000 members, published a Finnish translation of Mein Kampf, and held small rallies, but they won zero parliamentary seats and wielded no influence. During the Continuation War (1941–1944), Finland co-belligerented with Germany against the Soviet Union purely for survival after the Winter War invasion—Field Marshal Mannerheim’s government refused to join the Axis formally, declined to deport its Jewish citizens (nearly all survived), and maintained parliamentary democracy with elections in 1939 and 1945. Post-war, Finland paid reparations to the USSR but preserved its independence and democratic institutions, evolving into a Nordic social democracy. Finland’s enduring homogeneity and resilience stem from its constitutional framework and armed citizenry, not National Socialist ideology—much closer to our own Second Amendment traditions than to the Führerprinzip.

No regime has fully implemented National Socialism and prospered long-term. Like Marxist communism’s failed experiments—from the Soviet famines to Mao’s Cultural Revolution—NS bloomed in Germany’s post-Versailles humiliation but collapsed in twelve years amid total war. Its economy, initially boosted by public works like the Autobahns and Hjalmar Schacht’s deficit financing, proved unsustainable without plunder. Early funding came from industrialist donations and small-scale SA “expropriations,” but the war machine relied on occupation theft: over 600 million dollars in gold looted from central banks in Belgium, the Netherlands, and elsewhere, per Reichsbank ledgers. Jewish assets were seized en masse, but this was broad confiscation, not targeted Rothschild raids (a common myth; the family had scattered pre-1933). The “miracle” was debt-fueled illusion, bursting by 1943 as resources dwindled. Talent flourished in niches—like Wernher von Braun’s rocketry—but the system devoured itself through overreach.

Schacht’s MEFO Bills: The Hidden Debt Bomb of National Socialist Financing

The Nazi economic “miracle” of the mid-1930s—unemployment slashed from 6 million to near zero by 1938—relied not on sustainable productivity or trade, but on a elaborate financial subterfuge: the MEFO bills (Mefo-Wechsel), devised by Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht in 1934. These were promissory notes issued by a dummy shell company, Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft (MEFO), with a nominal capital of just 1 million Reichsmarks and no real operations. Armaments contractors received MEFO bills as payment for weapons production, which they could discount at private banks, and those banks could rediscount at the Reichsbank—effectively channeling billions in central bank credit to the government while bypassing legal limits.

Under Reichsbank statutes, direct lending to the government was capped at 100 million Reichsmarks. MEFO bills circumvented this, hiding rearmament spending from official budgets, foreign observers, and the Treaty of Versailles’ restrictions. By April 1938, 12 billion Reichsmarks in MEFO bills circulated—roughly equal to official government debt and a third of Germany’s GNP—fueling tanks, planes, and Autobahns without immediate inflation or visible deficits. Schacht himself admitted: this “device enabled the Reichsbank to lend by a subterfuge to the Government what it normally or legally could not do” (Nuremberg Document 3728-PS).

Yet this was no genius innovation, but a ticking time bomb. Bills matured in six months (extendable up to five years at 4% interest), creating hidden debt that demanded repayment through conquest. Schacht halted new issuances in March 1938, warning of overextension as reserves strained and full employment risked wage-price spirals. The regime rolled over bills, absorbed them into the Reichsbank, forced banks to buy bonds, raided savings/insurance funds, and pivoted to plunder: over 600 million dollars in looted gold from occupied central banks (Reichsbank ledgers). Without war victories, collapse loomed by late 1938, as detailed in Adam Tooze’s The Wages of Destruction.

This fiscal sleight-of-hand exemplifies National Socialism’s core peril: leader-dependent shortcuts over enduring institutions. Contrast our Founders’ republic, with its constitutional checks (e.g., Article I, Section 9 prohibiting unappropriated expenditures without Congress), debt limits via balanced powers, and no reliance on hidden “shell company” tricks. Ethnic American Constitutionalism demands transparency and restraint—qualities the Führerprinzip discarded, dooming the system to plunder-fueled fragility.

Anticipating Critiques: National Socialist Objections to the American Constitution—and the Day After

To engage fairly, let us address common arguments from National Socialist perspectives against our Constitutional Republic. Drawing from Hitler’s writings and NS theorists, critics often contend that the U.S. Constitution promotes harmful individualism, enabling plutocratic control and racial dilution. In Mein Kampf (Volume 1, Chapter 10), Hitler derided the American “melting pot” as suicidal, arguing the document’s emphasis on personal liberty fosters decadence over communal racial strength—allowing “Jewish” influences to infiltrate via free markets and speech. NS ideologues like Alfred Rosenberg echoed this, viewing separation of powers as paralyzing, preventing the decisive mobilization needed for a Volksgemeinschaft (people’s community). They saw federalism as fragmenting national unity, contrasting it with the centralized Reich that could enforce blood-and-soil purity. Another frequent critique is that Enlightenment individualism erodes tribal bonds, citing the Constitution’s lack of explicit racial provisions as a gateway to later dilutions like the 1965 Immigration Act.

These points merit serious reflection; the Constitution’s liberties have indeed been exploited in modern times, from unchecked immigration post-1965 to corporate globalism eroding our ethnic core. However, this misreads the document’s original intent and proven efficacy for our forebears. Crafted by white European men—English, Scots-Irish, Dutch, German—for their white posterity, it built the world’s mightiest nation through guarded individualism: Property rights spurred innovation (Hamilton’s system), while the Second Amendment armed citizens against tyranny. Separation of powers strengthened resolve, as seen in the Supreme Court’s 1935 Schechter Poultry ruling striking down FDR’s overreach. It rejected universalism—the 1790 Act’s racial citizenship clause ensured assimilation into our ethnic fold, and the “melting pot” Hitler mocked in the 1920s, referred exclusively to European immigrants (Irish, Italians, Germans), blending them into a unified white American identity without non-European influx. Where NS centralizes risk in one fallible leader, our framework distributes authority, enabling wolves like us to check threats internally. It secured a white-majority republic for 175 years, a record NS never matched. Moreover, its adaptability—through 27 amendments—allows rectification without the chaos of revolution, as evidenced by the 14th Amendment’s post-war reconstruction or the 21st’s Prohibition repeal. NS’s rigidity, by contrast, permitted no internal correction, leading to inevitable overreach and downfall.

A deeper oversight in the NS vision—one rarely confronted—is the question of governance after the revolution: What blueprint guides the new order? Ethnic American Constitutionalism provides an immediate, refined framework: We inherit a proven charter, ready to restore via targeted reforms. Overturn post-1868 amendments like the 14th (misapplied to birthright citizenship for invaders) or 15th (universal male suffrage diluting our ethnic voice), and bolster racial and religious language by invoking the Federalist Papers—Madison’s No. 10 on controlling factions through republican safeguards—and Elliot’s Debates (the 1787–1788 ratification records, where Anti-Federalists like Patrick Henry demanded explicit protections for our Christian, white posterity, yielding the Bill of Rights’ religious establishments clause). State conventions could amend swiftly, nullifying federal overreach per Jefferson’s Kentucky Resolutions, all within the existing structure. This is evolution, not invention—our ethnic republic, recalibrated for 21st-century threats.

National Socialism, however, offers fragments: The 25-Point Program (1920 manifesto demanding racial purity and land reform), Mein Kampf’s polemics, and the Organisationsbuch der NSDAP (annual Organization Book, edited by Robert Ley from 1934 onward, detailing party bureaucracy, uniforms, and administrative hierarchies like Gauleiter districts). It’s a operational manual for a Führer-centric machine—hundreds of pages on rituals and ranks, but no enduring civic code for disputes, economies, or succession beyond the Leader’s whim. David Lane’s 88 Precepts add timeless axioms on natural law and race, but they are inspirational sketches, not a constitutional scaffold. Post-revolution, what arbitrates power struggles? Who drafts laws for a post-Führer world? The vacuum invites feuds, as seen in the Night of the Long Knives’ internal bloodletting. Our path builds on 248 years of tested resilience; theirs risks reinventing the wheel amid rubble.

Comparisons to the Weimar Republic’s Government

A related claim sometimes surfaces: that the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) had a “carbon copy” of the U.S. Constitution—a claim made since the 1950s, and its collapse under the Versailles Treaty, Dawes Plan, and Young Plan reparations proves the American system inevitably leads to the same subversion we face today—while Germany “solved” it through National Socialism. This argument is worth examining in detail, as it strikes at the heart of why our framework remains superior.

The Weimar Constitution was not a carbon copy of the American one. It was a hybrid semi-presidential parliamentary system drafted primarily by Hugo Preuss, who drew partial inspiration from the U.S. (federal elements, a bill of rights, bicameral legislature) but far more from the failed Frankfurt Constitution of 1849 (Germany’s liberal unification attempt after the 1848 revolutions) and European models like France and Belgium. Key structural differences made Weimar extraordinarily vulnerable to subversion—flaws the U.S. Constitution deliberately avoids:

- Proportional Representation (PR) vs. Winner-Take-All Districts: Weimar used pure proportional representation with almost no threshold (until a weak one in 1933). Any party getting roughly 0.7 percent of the vote won seats, routinely producing 15–20 parties in the Reichstag. Coalitions were fragile; governments collapsed frequently, creating paralysis. The U.S. uses single-member districts and first-past-the-post voting, crushing small extremist parties and forcing broad coalitions—typically two major ones. Even during crises like the Great Depression, America never faced Weimar-level fragmentation.

- Article 48 – the Emergency Decree Clause: Weimar’s president could suspend civil liberties and rule by decree in “states of emergency.” From 1930 onward, chancellors like Brüning governed almost entirely this way; Hitler legalized total power through it in 1933. The U.S. Constitution has no equivalent broad emergency clause allowing the president to bypass Congress or courts indefinitely.

- Weak Checks and Balances: Weimar’s upper house (Reichsrat) was powerless compared to the U.S. Senate. There was no strong independent constitutional court to strike down decrees. The U.S. Supreme Court provides judicial review; the Senate is co-equal.

These design flaws—especially PR and Article 48—turned economic stress (reparations, hyperinflation) into political chaos. Versailles crippled Weimar, but the constitution’s structure enabled its downfall. Germany “got rid” of the problems by defaulting on reparations, rearming, and launching war—hardly a superior outcome, ending in total defeat, 70+ million dead, partition, and occupation.

The American system, by contrast, has weathered comparable crises (Civil War, Great Depression, 1960s turmoil) without legal dictatorship or collapse. Later amendments and interpretations have indeed enabled subversion, but the core 1787 design—winner-take-all districts, no emergency decree power, strong bicameralism—resists the paralysis that doomed Weimar.

These points merit serious reflection; the Constitution’s liberties have indeed been exploited in modern times, from unchecked immigration post-1965 to corporate globalism eroding our ethnic core. However, this misreads the document’s original intent and proven efficacy for our forebears. Crafted by white European men—English, Scots-Irish, Dutch, German—for their white posterity, it built the world’s mightiest nation through guarded individualism.

Our Shared Faith: Christianity as the Bedrock of American Identity

Lastly, I understand the skepticism some hold toward Christianity, viewing it as a diluted form of Judaism that has historically allowed external influences to infiltrate societies. The critique that we follow a figure—Jesus Christ—born Jewish carries weight for those prioritizing a purely pagan or racialist worldview. It is a perspective worth considering, as it stems from a desire to reclaim unadulterated European traditions. However, from my standpoint as a committed Constitutionalist, America’s founding was indelibly Christian—not as a passive import, but as a robust framework tailored to our white European forebears, serving as a moral and cultural fortress for their posterity.

The evidence is embedded in our foundational texts and practices. John Jay, in Federalist No. 2, described the American people as united by common ancestry, language, and religion—predominantly Christian, with over 98 percent of the population professing it in 1787. James Madison, in Federalist No. 37, attributed the Constitution’s creation to divine guidance from “that great Being who created the universe.” Every original state constitution invoked Christian principles: Delaware required officeholders to affirm belief in the Trinity; Massachusetts established Protestant teachings in schools and barred atheists from public roles; Pennsylvania pledged fidelity to “one God” and the divine Scriptures. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 promoted “religion, morality, and knowledge” as essential to good government, with “religion” understood as Christianity.

The Founders themselves embodied this: George Washington invoked “Divine Providence” in his Farewell Address; John Adams asserted that the Constitution was made only for a “moral and religious people,” with Christianity as its underpinning; Benjamin Franklin proposed daily prayers at the Constitutional Convention “in the name of Jesus Christ, the Mediator.” Thomas Jefferson’s famous “wall of separation” letter (1802) protected Baptist freedoms from state interference, not religion from governance—his Declaration of Independence grounded rights in a Creator God, echoing Christian natural law from thinkers like Aquinas. The 1790 Naturalization Act, limiting citizenship to free white persons of good character, implicitly favored Christian Europeans renouncing foreign allegiances.

This Christian foundation was no accident; it fortified a nation for our ethnic kin—white settlers who built churches alongside homesteads, infusing frontier life with a faith that emphasized personal responsibility, community solidarity, and resistance to tyranny. It is the fire that powered our Revolution, not a weakening agent. While I respect alternative views on its origins, this heritage aligns with our American identity far more than imported ideologies.

Our True Heroes and the Path Forward

I understand the magnetic pull of NS icons—their era’s vivid records capture a fervor absent from Revolutionary sketches. Yet our heroes eclipse them in substance: George Washington, who quelled a potential coup and surrendered his sword to preserve the republic. Thomas Jefferson, architect of the Declaration and defender of states’ rights against federal encroachment. James Madison, the Constitution’s father, who balanced union with liberty. These men—our ethnic kin—faced redcoats over a tea tax, debated in sweltering halls, and forged a nation for white Americans.

Reclaiming this republic means recommitting to 100 percent Constitutional fidelity: Enforce the 1790 Act’s spirit through border nullification, revive founders’ intent via amendments, and mobilize our people as armed sovereigns. Resources like EthnicAmerican.org’s history series detail our suppressed identity—from pioneer ethnogenesis to the 1965 “displacement.” We are not 1940s Germans; we are the wolves of 1776, heirs to a white state. Let us build on that unyielding ground.

Brothers, the fight is ours. Join in preserving what was won for us.

© James Sewell 2025 – All rights reserved

I want to to thank you for this wonderful read!! I certainly enjoyed every bit of it. I’ve got you bookmarked to check out new things you

Pingback:The Ethnic American Library - Ethnic American