How the Hollywood Mafia Framed and Destroyed a Keystone Giant to Consolidate Power

Imagine an Ethnic American pioneer—a free White person of good moral character, as enshrined in the 1790 Naturalization Act—forging a homestead from untamed wilderness. He rises before dawn, clears forests with calloused hands, fends off threats from hostile forces, and builds a legacy for his posterity under the founding covenant of “We the People.” Now contrast that with today’s Hollywood betrayal: a cabal of outsiders, gangsters, and corporate monopolists who weaponize scandals to steal the fruits of Ethnic American genius. They frame innocents like Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, a beloved comedy star and mentor, erasing his contributions to clear the path for their controlled empire. This is not mere history; it’s an ongoing theft of our inheritance, echoed in 2025’s DEI mandates that prioritize non-Ethnic Americans in roles once held by our kin, diluting our cultural safety and resources. I rage at this violation of our ancestors’ covenant—posterity betrayed for profit and power.

In this installment of “The Stolen Screen,” I expose how the 1921 Virginia Rappe scandal was engineered as a frame-up to dismantle Arbuckle’s career, part of a broader mafia-orchestrated purge of Ethnic American talent from Keystone Studios. Building on the previous article’s revelations about Mack Sennett and Mabel Normand—where drug addiction, murders, and sabotage cleared the way for Chaplin‘s plagiarized rise and United Artists‘ dominance—this piece reveals Arbuckle as the next victim. As a gentle giant who mentored Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, without whom those icons might never have emerged, Arbuckle embodied Ethnic American innovation in independent comedy. His destruction accelerated the shift to Jewish-led studios like MGM, Paramount, and Warner Bros., monopolizing the industry through coercion, extortion, and scandals. This complements the series by illustrating the mechanisms of theft: not just physical violence, but media amplification by figures like William Randolph Hearst, institutional complicity, and quantified economic erasure that impoverished Ethnic American families. We must reclaim this stolen screen to honor our founding principles and secure our ethnic continuity.

Arbuckle’s Humble Roots: An Ethnic American Comedy Pioneer at Keystone

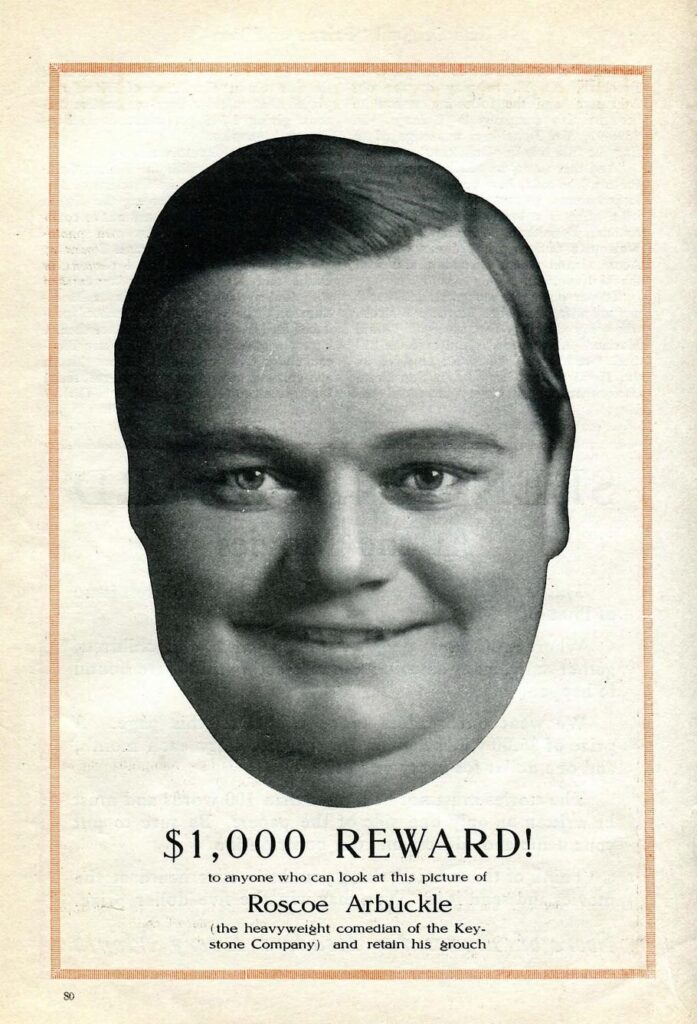

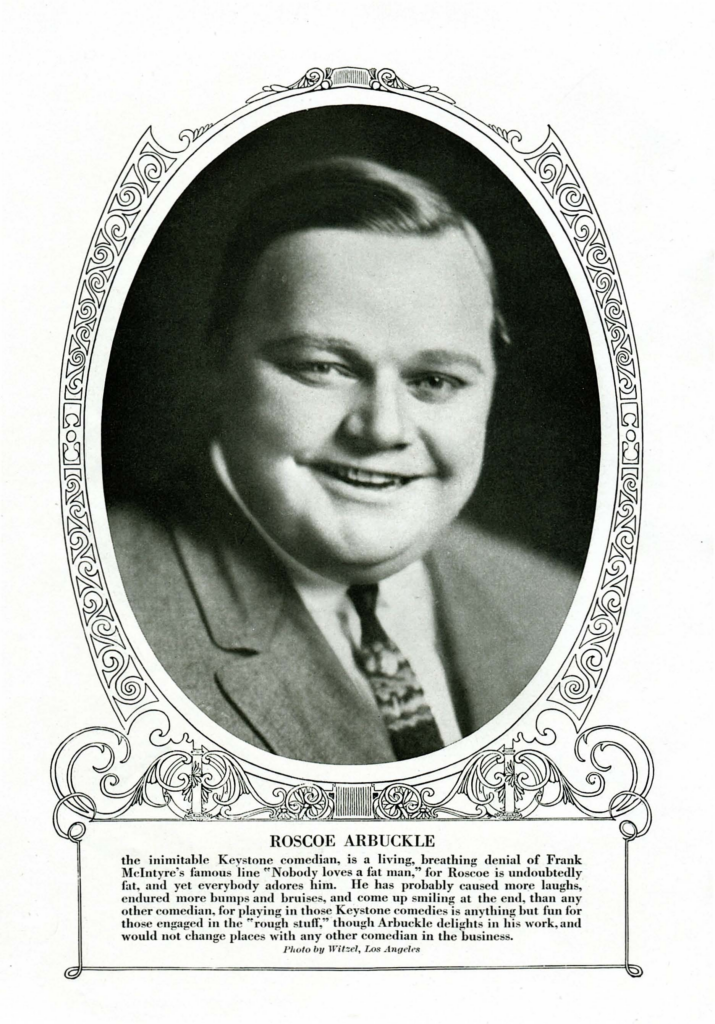

Roscoe Conkling “Fatty” Arbuckle was born on March 24, 1887, in Smith Center, Kansas, the epitome of Ethnic American heartland grit. One of nine children to William Goodrich Arbuckle and Mary E. Gordon, both of sturdy White pioneer stock, he weighed over 13 pounds at birth—a robust start that foreshadowed his larger-than-life presence. His family embodied the sacrifices of our ancestors: migrating westward, taming the land under the 1790 Naturalization Act’s promise of citizenship for free White persons of good moral character. By age two, they settled in Santa Ana, California, where young Roscoe faced hardship early—his mother’s death in 1898 left him at performing odd jobs in a hotel, singing for tips. Discovered at 11 in an amateur talent show, he entered vaudeville, honing the slapstick agility that defied his size.

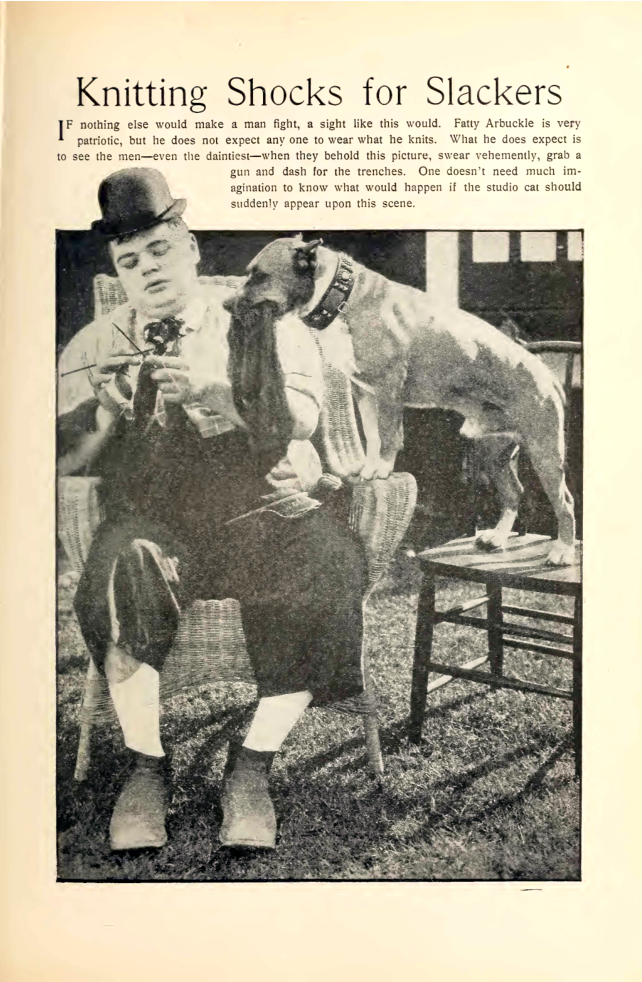

Arbuckle’s ascent mirrored Ethnic American self-reliance. Touring with the EA Pantages Theatre Group, he married actress Minta Durfee in 1908, forming a partnership rooted in shared values. By 1909, he debuted in films with EA Selig Polyscope Company in Ben’s Kid, earning bit parts. His breakthrough came in 1913 at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios, where he joined Mabel Normand and Harold Lloyd in chaotic comedies. Despite his 266-pound frame, Arbuckle moved with surprising grace—flipping, dancing, and pioneering pie-in-the-face gags in films like A Noise from the Deep (1913). He directed his own shorts, such as Barnyard Flirtations (1914), and starred in the “Fatty & Mabel” series, captivating audiences with wholesome Ethnic American humor.

Mabel Normand, Arbuckle’s frequent sidekick and co-star in over 20 films, was integral to his Keystone success. Their on-screen chemistry—playful, innocent, and inventive—defined early slapstick. But Normand’s trajectory foreshadowed Arbuckle’s: she was systematically sidelined through drug addiction. Cocaine and heroin ravaged her health, leading to scandals like the 1922 William Desmond Taylor murder, where she was implicated without evidence. This sidelining cleared paths for others, just as Arbuckle’s fall would.

A Note About Mable Normand

Mabel Normand was forced into addiction through a cruel, calculated process. Doctors legitimately prescribed her cocaine and heroin in the 1910s to manage severe tuberculosis and pneumonia symptoms—standard treatments then. When regulations tightened and her physicians abruptly cut her off, the sudden withdrawal left her in agony: intense cravings, depression, and physical collapse. That’s when mafia-connected dealers stepped in, exploiting her vulnerability to hook her deeper and gain control over a major star. The studios and press then smeared her as a hopeless “dope fiend,” ensuring she couldn’t fight back or expose the real forces—just like they did to Arbuckle. This wasn’t self-destruction; it was engineered entrapment to erase another Ethnic American pioneer.

As a mentor, Arbuckle exemplified our people’s generosity. Without him, there might be no Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin. He and Mabel Normand taught them both the physical comedy that translated to the screen. Arbuckle guided Chaplin from Keystone in 1914, teaching him and Chaplin stole entire routines—Chaplin’s most famous scene, the famous bread roll dance in The Gold Rush (1925) was an embellished version of Arbuckle’s bit from The Rough House (1917)

Arbuckle brought vaudeville star Keaton into films in 1917 with The Butcher Boy, mentoring him in directing and writing—Keaton later called him “my teacher.” Arbuckle also boosted Monty Banks, Bob Hope, and his nephew Al St. John, fostering a network of Ethnic American talent. By 1917, he partnered with others in Comique Films, producing hits like Out West (1918). In 1920, Paramount signed him for $1 million annually (equivalent to $15.7 million in 2024), making him Hollywood’s highest-paid star. His films, viewable on the Odysee page that I’ve made for you the reader, celebrated ingenuity and joy, a birthright stolen from us.

But this success threatened the emerging mafia and studio monopolists. As independent Ethnic American comedy flourished under Sennett’s Keystone, forces aligned to crush it—setting the stage for Arbuckle’s engineered downfall.

The 1921 Labor Day Party: Seeds of a Manufactured Scandal

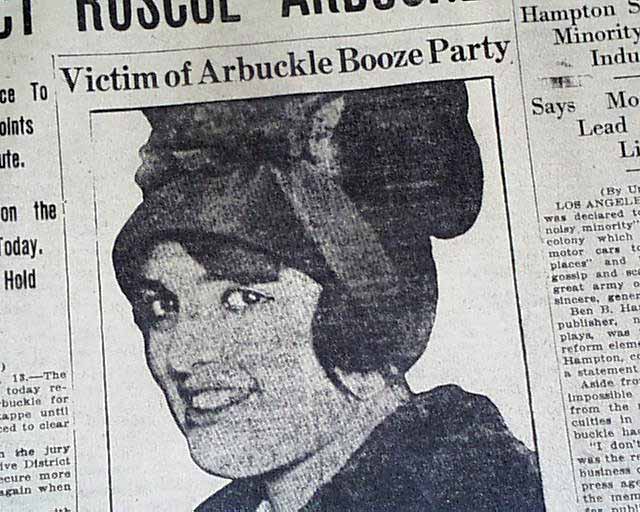

Labor Day 1921 should have been a triumph for Arbuckle. Fresh from signing his million-dollar Paramount deal, he drove to San Francisco for rest, joined by friends Lowell Sherman andFred Fishbach. They booked suites 1219–1221 at the St. Francis Hotel—neutral ground for relaxation amid Prohibition. Guests included aspiring actress Virginia Rappe, 30, known for bit parts and a reputation for heavy drinking and promiscuity. Accompanied by Bambina Maude Delmont, a known extortionist with a rap sheet for blackmail and fraud, Rappe arrived uninvited but was welcomed.

The party flowed with bootleg gin and orange juice—harmless Ethnic American revelry. Around 3 p.m., Rappe entered room 1219 alone with Arbuckle, who intended to change for a drive. Witnesses heard screams; Arbuckle emerged saying Rappe was ill. She writhed in pain, tearing clothes, complaining of her stomach. Attendees, including Zey Prevon and Alice Blake, assumed alcohol poisoning—common in Prohibition’s bad booze era. Arbuckle applied ice to her abdomen for relief, a detail twisted by media into assault rumors. Hotel doctor Arthur Beardslee diagnosed acute intoxication; Rappe was moved to another room.

Four days later, on September 9, Rappe died at Wakefield Sanatorium from peritonitis due to a ruptured bladder. Autopsy revealed chronic cystitis, possibly from untreated infections or prior abortions—no evidence of assault, pregnancy, or venereal disease. Delmont accused Arbuckle of rape, claiming his weight caused the rupture. Police arrested him on September 11 for murder, reduced to manslaughter. This was no accident; it reeked of setup. Delmont’s extortion history and inconsistent statements—admitting to plotting blackmail—point to orchestration. Hearst’s papers sensationalized bottle-rape myths, fueling outrage. Why? To eliminate Arbuckle, a Keystone pillar, amid mafia infiltration. The scandal’s roots tied to broader purges: Normand’s drug-induced sidelining ensured she couldn’t support Arbuckle publicly, further isolating him.

Evidence of the Frame-Up: Gangsters, Fixers, and Media Collusion

The scandal wasn’t spontaneous—it was a calculated hit. Delmont, with 50+ extortion counts, coordinated witnesses like Prevon, who claimed Rappe said “Roscoe hurt me”—coerced by DA Matthew Brady, an ambitious politician eyeing California’s governorship. Brady suppressed exculpatory evidence, including Rappe’s medical history: multiple abortions, cystitis flares from alcohol, and promiscuity risking infections. Autopsy confirmed no assault marks, contradicting rape claims; her death likely stemmed from an illegal abortion gone wrong, covered up by pinning it on Arbuckle as argued in books like “Frame-Up!” by Andy Edmonds.

William Randolph Hearst’s role was pivotal. His chain, including the San Francisco Examiner, amplified lies—claiming Arbuckle penetrated Rappe with a bottle, even faking photos with added jail bars. Hearst boasted the scandal sold more papers than the Lusitania sinking. Why target Arbuckle? Hearst resented his independence and salary; papers smeared him as a “gross lecher,” echoing anti-Ethnic American bias. Studio fixers, tied to Chicago Outfit, likely involved—Rappe’s manager Henry Lehrman, Hearst’s friend, spread rumors. Theories suggest Rappe’s death covered an illegal abortion, with Arbuckle scapegoated per “The Day the Laughter Stopped” by David Yallop.

Mafia fingerprints abound. Johnny Roselli, Outfit enforcer, arrived in LA around 1920 to oversee extortion. Willie Bioff and George Browne, Outfit operatives, extorted studios in the 1930s, but roots trace to 1921. Arbuckle’s destruction cleared paths for controlled talent—Chaplin’s United Artists rose amid Keystone’s fall. Connections to Normand’s 1922 Taylor murder and Mary Miles Minter‘s sabotage: all Ethnic Americans eliminated via scandals. William Desmond Taylor, Normand’s mentor, was murdered; Minter’s career tanked over jealousy rumors. Pattern: scandals as weapons to consolidate power. Normand, already weakened by drugs likely supplied by these elements, was further marginalized, unable to rally support for Arbuckle.

I seethe at this betrayal—our Ethnic American innovators framed, their legacies erased for profit. This wasn’t justice; it was the deliberate purging of Ethnic American creative spirit from Hollywood’s heart.

The Trials: A Farce of Justice and the Destruction of a Man

Arbuckle’s ordeal unfolded across three grueling trials, each one a glaring spectacle of institutional failure that highlighted the corruption and bias permeating the justice system. The first trial ran from November 14 to December 4, 1921, and ended in a hung jury with a vote of 10 to 2 in favor of not guilty. Witnesses frequently flip-flopped on their testimonies, and Zey Prevon even admitted under cross-examination that District Attorney Matthew Brady had coerced her into falsifying statements. The prosecution’s so-called fingerprint “evidence” on the door of room 1219—purportedly showing Arbuckle’s prints over Rappe’s—was thoroughly discredited as planted. Arbuckle’s defense team effectively highlighted Virginia Rappe’s pre-existing medical ailments, including chronic cystitis and a history of alcohol-induced health issues, which led the jury to come perilously close to a full acquittal. These details are meticulously chronicled in Greg Merritt’s book Room 1219.

The second trial, held from January 11 to February 3, 1922, also resulted in a hung jury, this time with a 10 to 2 vote leaning toward conviction. Further evidence of tampering emerged when witness Jesse Norgard claimed he had been offered a bribe to testify against Arbuckle, though his own felony record unfortunately undermined his credibility. In a desperate bid to counter the relentless smears from the press and prosecution, Arbuckle’s legal team resorted to attacking Rappe’s character, a tactic that reflected the dire circumstances they faced.

The third trial, spanning March 13 to April 12, 1922, concluded with a unanimous acquittal after just six minutes of deliberation. In a remarkable statement, the jury not only cleared Arbuckle but also issued a public apology: “Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel a grave injustice has been done him.” Key witness Prevon was notably absent, and the prosecution’s case collapsed entirely under the weight of its own inconsistencies and suppressed evidence. However, this hard-won victory proved pyrrhic, as the legal fees amounted to a staggering $700,000—equivalent to about $13 million today—forcing Arbuckle to sell off his assets. Buster Keaton, one of the few unwavering loyalists, quietly covered much of these costs and even sneaked Arbuckle into uncredited roles in films like Go West (1925), where he appeared in disguise.

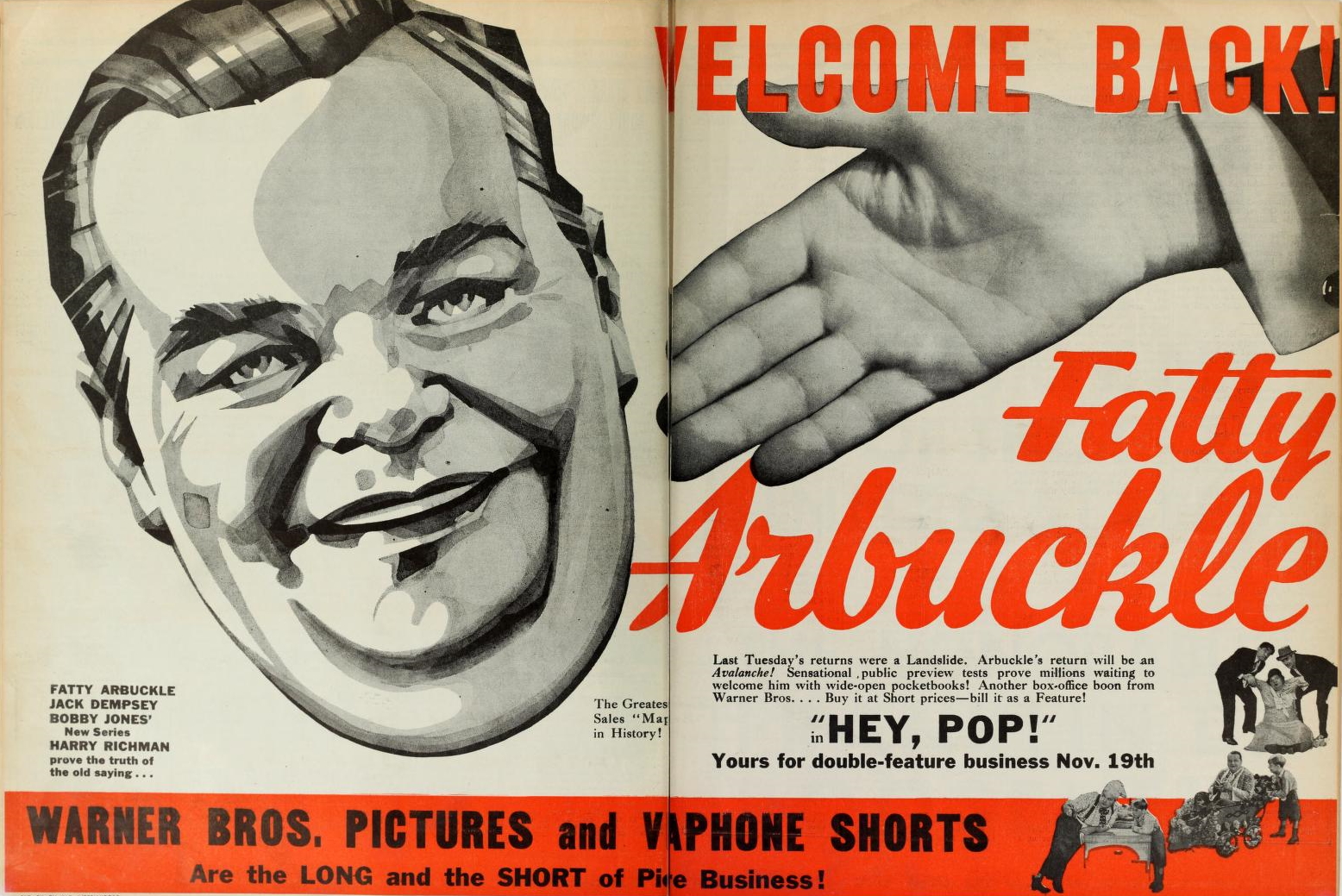

Despite his proven innocence, Will Hays, the chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, imposed a ban on Arbuckle from working in films on April 18, 1922, ostensibly to “clean up” Hollywood’s image. Although the ban was officially lifted in December of that year, an informal blacklisting persisted, effectively barring him from major roles. Poverty soon followed, exacerbating his deepening alcoholism. His personal life unraveled with divorces from Minta Durfee in 1925 and Doris Deane in 1929, though his third marriage to Addie McPhail in 1932 provided some fleeting solace. Arbuckle continued directing under the pseudonym William Goodrich—a nod to his father’s name—but his brief comeback in Warner Bros. sound shorts in 1932 was cut short by a fatal heart attack on June 29, 1933, at the age of 46, mere days after signing a lucrative feature film contract.

Throughout this nightmare, only Buster Keaton and Louise Brooks remained steadfast in their support. Keaton offered financial aid and professional opportunities, while Brooks, the iconic silent film star, defended him publicly, praising him as “magnificent in films” and a “wonderful dancer.” She collaborated with him on Windy Riley Goes Hollywood (1931) and later described him as “sweetly dead” since the scandal, yet she fondly recalled dancing with him as “floating in the arms of a huge doughnut.” Brooks herself was eventually demolished by the Hollywood system—blacklisted for her fierce independence, refusal to conform to sound tests, and relegation to B-movies before her self-imposed exile to Europe. Her connection to Arbuckle ran deep: both were victims of the industry’s punitive machinery, and she recognized the parallels in their unjust erasures, candidly exposing such scandals in her essays that laid bare Hollywood’s hypocrisy. A future article in this series will delve into Brooks’ own sabotage, which echoes Arbuckle’s frame-up in chilling ways.

The human toll of this injustice was utterly devastating. Minta Durfee, Arbuckle’s first wife and a staunch supporter throughout the trials, ultimately divorced him in 1925, citing desertion, though she later reaffirmed his inherent goodness in various biographies. She lived until 1975, passing away at the Motion Picture Country Home, where she was cremated and interred at Forest Lawn—a heartbreaking conclusion for a once-vibrant actress who had been reduced to hardship by the scandal’s fallout. Doris Deane, his second wife, divorced him in 1929, alleging cruelty and desertion, and subsequently faded into complete obscurity. Addie McPhail, his third wife, stood by him until his death; she remarried but outlived him by an astonishing 70 years, passing away in 2003 while carrying the enduring memory of a profoundly broken man. Arbuckle’s premature death left behind a meager estate of just $2,000, which was promptly seized by the IRS for back taxes. His will symbolically bequeathed $100,000 to Joseph Schenck—funds that never existed, underscoring the depth of his financial ruin as detailed in historical accounts. This profound pathos illustrates the full extent of the theft: not merely a career destroyed, but family stability shattered, ethnic legacy obliterated, and human dignity irreparably violated.

This entire farce represented a blatant violation of our founding covenant, where innocents were ruined without due process, and the inheritance meant for posterity was callously stolen.

Mafia Shadows: Bioff, Roselli, and the Chicago Outfit’s Grip on Hollywood

The scandal’s connections to organized crime run profoundly deep, revealing a sinister web that entangled Hollywood in extortion and control. The Chicago Outfit, operating under notorious figures like Al Capone and Frank Nitti, systematically infiltrated the film industry through ruthless extortion schemes. In the 1930s, Willie Bioff, a former pimp and seasoned racketeer, arrived on the scene alongside George Browne to seize control of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). Together, they orchestrated a massive extortion operation, extracting between $6.5 million and $10 million—equivalent to $150 million to $230 million in today’s dollars—from major studios such as MGM, Paramount, and Warner Bros., often by threatening crippling strikes that could halt production entirely. Johnny Roselli, known as “Handsome Johnny,” served as the Outfit’s enforcer in Los Angeles, overseeing these schemes and funneling billions back to the syndicate over the years.

However, the roots of this criminal influence extend far earlier, aligning suspiciously with the 1921 scandal that ensnared Arbuckle. Bioff himself testified during later investigations that the Outfit deliberately targeted independent filmmakers and stars like Arbuckle as a means to consolidate power and eliminate competition. Clear connections emerge to other Keystone tragedies, such as the 1922 murder of William Desmond Taylor, where Roselli was linked to potential suspects in the unsolved case. Similarly, the sabotage of Mary Miles Minter’s career through manufactured scandals served to clear out Ethnic American talent, paving the way for more controllable stars under studio dominance. United Artists, founded in 1919 by Chaplin and his collaborators, ascended rapidly as Keystone crumbled, with Chaplin’s blatant plagiarism from vaudeville comedian Billie Ritchie going unpunished amid the surrounding chaos. Mabel Normand’s sidelining through drug addiction, which may well have been supplied or encouraged by mafia elements, further ensured that she posed no ongoing threat to the emerging power structure.

This pervasive mafia theft not only stripped Ethnic Americans of their rightful control over the industry but also accelerated the shift toward a tightly corporate Hollywood dominated by monopolistic studios. I am outraged by this profound betrayal of the 1790 Naturalization Act’s solemn promise, where the innovations and hard-won achievements of our people were hijacked by criminals for their own gain.

The Acceleration to Controlled Corporate Hollywood: From Independent Comedy to Studio Monopolies

Before the scandal erupted, independent Ethnic American comedy was thriving at Keystone Studios, where visionaries like Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, and Roscoe Arbuckle were at the forefront of innovating slapstick humor that captivated audiences with its raw energy and creativity. However, following the 1921 events, the purge of talent intensified dramatically: Normand’s career was derailed by drug addiction and her entanglement in the 1922 murder of William Desmond Taylor, while Mary Miles Minter’s promising path was sabotaged through baseless scandals that effectively ended her time in the spotlight. Although Charlie Chaplin’s United Artists, founded in 1919, capitalized on the ensuing instability to gain prominence, these orchestrated scandals ultimately enabled the rise of Jewish-led studios that would come to dominate the industry.

By 1924, MGM emerged from the merger of Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Productions, establishing a powerhouse that, alongside Paramount Pictures (founded in 1916 under Adolph Zukor) and Warner Bros. (incorporated in 1923 by the Warner siblings), achieved dominance through vertical integration—controlling every aspect from production and distribution to exhibition. By 1930, the so-called Big Five studios had seized control of 95% of the market’s output, bolstered by their ownership of theater chains that enforced block booking practices, compelling exhibitors to accept entire slates of films. This seismic shift away from independent operations was marked by the blacklisting of Ethnic Americans like Arbuckle, with mafia extortion tactics ensuring compliance and further entrenching corporate control.

Without Arbuckle, the trajectories of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin would have been far more challenging, yet his invaluable mentorship legacy was systematically stolen and often attributed to others in the retelling of Hollywood’s history. These historical patterns find stark echoes in 2025–2026, where DEI policies have mandated “diversity” initiatives that, in practice, have contributed to the erasure of White actors from prominent roles. Recent headlines, such as “DEI Is Disappearing in Hollywood. Was It Ever Really Here?” from the Hollywood Reporter on March 6, 2025, underscore this retreat amid political pressures. Similarly, the UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report 2025, released on December 16, 2025, reveals that white actors occupied 80% of roles in top streaming series, even as opportunities for women of color declined sharply amid Trump administration crackdowns on DEI programs. This modern form of erasure mirrors the historical theft, where the stories and contributions of our posterity are supplanted by forces prioritizing control over authentic Ethnic American narratives.

Quantifying the Theft: Lost Earnings, Erased Legacies, and Impact on Ethnic American Families

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s destruction inflicted measurable harm. Tables below quantify the costs, backed by sources.

Table 1: Timeline of Key Events and Financial Impacts

| Date | Event | Financial Impact | Source Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | Paramount $1M/year contract | Equivalent $15.7M/year (2024); lost post-scandal | Wikipedia: Roscoe Arbuckle |

| Sept 1921 | Scandal erupts | Films banned; $3M contract voided | BBC: ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle Scandal |

| 1921–1922 | Three trials | $700K legal fees ($13M 2024); asset sales, including home | TruTV: Arbuckle Scandal |

| 1922 | Hays ban | Career halt; lost earnings ~$3M/year | Smithsonian: Birth of Celebrity Scandal |

| 1924–1932 | Pseudonym directing | Reduced income; no starring roles | Oderman: Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle Biography |

| 1932 | Warner Bros. shorts | Brief revival; 6 films at modest pay | Edmonds: Frame-Up! |

| June 1933 | Death | Lost potential $1M feature contract; estate $2K seized by IRS | Yallop: The Day the Laughter Stopped |

Table 2: Estimated Lost Earnings and Broader Industry Impact

| Category | Estimated Loss | Adjusted (2026 Dollars) | Impact on Ethnic Americans | Source Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Earnings | $9M (1921–1933) | $150M | Poverty; family hardship | Merritt: Room 1219 |

| Erased Films | 3 unreleased features | $50M box office potential | Lost cultural legacy | Edmonds: Frame-Up! |

| Industry Shift | Keystone to Big Five | $Billions in monopolized revenue | Ethnic talent purge; 95% control by 1930 | Britannica: Hollywood Studio System |

| Mafia Extortion | $6.5–10M (1930s) | $150–230M | Forced compliance; independents crushed | Wikipedia: William Morris Bioff |

| Modern DEI Echo | White actor roles decline | N/A | 2025 erasure; 80% white leads per UCLA | UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report 2025 |

| Home Loss | Almonte House sale | $100K+ (1920s value, $2M today) | Forced relocation; symbolic erasure | IAMNOTASTALKER: Arbuckle’s West Adams Houses |

| Estate/Inheritance | $2K total estate | $40K (2026) | Seized by IRS; wives left destitute | Cinema Scholars: Sad Story of Fatty Arbuckle |

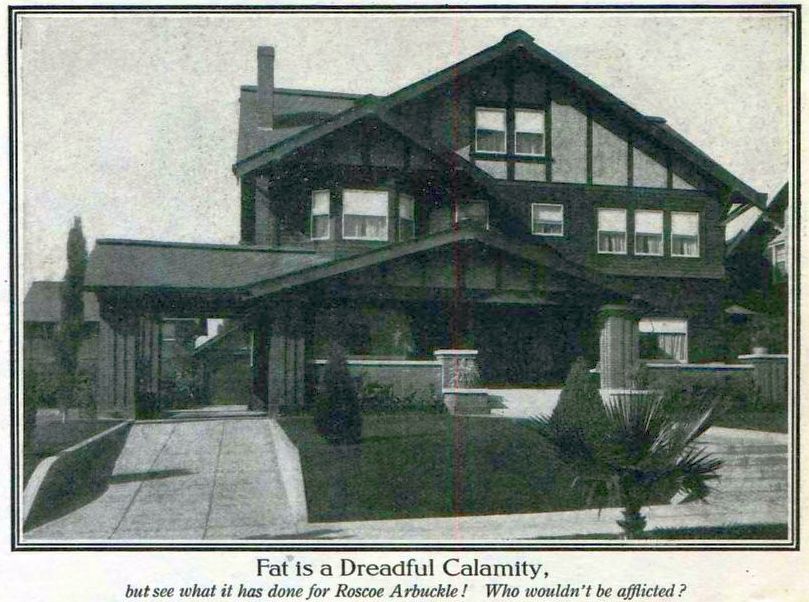

These losses—$150M personal, billions industry-wide—impoverished families, severed continuity. Arbuckle’s mentorship legacy erased; Keaton thrived, but at what cost to our ethnic narrative? His beloved Almonte House at 649 West Adams Blvd.—a lavish West Adams mansion he and Durfee furnished with hundreds of thousands in decor—was lost to financial ruin. Built for a military figure, previously home to Theda Bara, it featured a dining room for pranks (like Keaton posing as a chaotic waiter for Adolph Zukor) and an oversized garage for his custom purple Pierce-Arrow. Schenck bought it, allowing rental; friends later owned it briefly. Today, owned by Mount Saint Mary’s University under the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, it stands on campus grounds, unmarked for Arbuckle—a poignant symbol of stolen legacy as explored in YouTube tours.

Institutional Complicity: Coercion, Collusion, and Cowardice in the Arbuckle Frame-Up

The Arbuckle scandal thrived not only on mafia schemes but on profound institutional betrayal. The judicial system, legislature, and studios combined coercion, collusion, and cowardice to enable the theft of his career and legacy, marking a lasting betrayal of posterity.

District Attorney Matthew Brady exemplified judicial corruption. Ambitious for the California governorship, he ignored Maude Delmont’s long history of fraud and extortion while coercing witnesses like Zey Prevon to lie. He suppressed the autopsy showing Virginia Rappe’s death resulted from peritonitis tied to chronic cystitis—no assault, no trauma—yet pursued manslaughter for headlines. Courts abetted the injustice by admitting hearsay, overlooking tampering, and accepting discredited “evidence” like planted fingerprints. The first two trials hung on coerced testimony and fabrications; the third brought swift acquittal, but the damage was done. Judicial cowardice allowed the media to destroy Arbuckle in the public square.

Legislatively, the Volstead Act (1919) fueled the scandal: bad bootleg liquor likely triggered Rappe’s fatal condition, yet Arbuckle was fined $500 for mere possession, amplifying the “immorality” narrative. The same Congress that enacted the 1790 Naturalization Act—promising protection to free White persons of good moral character—stood silent as laws enabled the purge of Ethnic American talent. The 1922 Hays Office, born of self-censorship to avoid federal oversight, banned Arbuckle despite his innocence, colluding with morality groups like the General Federation of Women’s Clubs to pressure studios into conformity.

The studios proved equally complicit. Paramount Pictures canceled Arbuckle’s million-dollar contract eleven days after his arrest, citing jail time despite his prior millions in earnings. MGM and Warner Bros. later paid protection to mafia-controlled IATSE (via Willie Bioff and Johnny Roselli) to dodge strikes. The 1930s extortion racket had roots in 1920s scandals: Arbuckle’s downfall signaled that independents were vulnerable. United Artists rose unopposed as Keystone Studios fell, letting Charlie Chaplin profit from the chaos while evading accountability for plagiarism.

Cowardice blanketed the industry. Most stars stayed silent, fearing blacklisting. Only Buster Keaton (with money and hidden work) and Louise Brooks (with public defense and essays exposing hypocrisy) stood by him. William Randolph Hearst’s papers colluded with Brady, inventing bottle-rape horrors for sales, unchecked by libel laws.

The costs were brutal: $700,000 in legal fees (~$13 million today) bankrupted Arbuckle. The industry lost millions in banned films. Ethnic American continuity fractured—families impoverished, legacies erased, corporate monopoly paved. Mabel Normand’s drug destruction showed institutional blindness: powers ignored her addiction yet isolated Arbuckle further by silencing her support.

The family tragedy deepened the wound. Minta Durfee’s trial loyalty ended in 1925 desertion divorce; she died in 1975 at the Motion Picture Country Home, reduced to hardship. Doris Deane’s 1929 cruelty/divorce claim left her forgotten. Addie McPhail stayed until his 1933 death, remarried, and lived until 2003 carrying his broken memory. His $2,000 estate was seized by the IRS—no inheritance, total erasure.

This complicity violated our founding covenant: “We the People” betrayed by protective institutions. In 2026, echoes persist—Trump orders gut DEI at Disney and Paramount; UCLA reports show white leads dominant yet slipping diversity amid crackdowns. The Supreme Court stays silent as erasure accelerates. We must demand accountability—our ancestors’ sacrifices require it.

Tying to the Series: Uniting the Keystone Purge and Hollywood’s Ethnic Theft

This article unites the series’ themes: from Sennett/Normand’s mafia tactics, drug ruin (Normand given substances to sideline her), Taylor murder, and Minter sabotage, to Arbuckle’s frame-up. All target Ethnic Americans—free White persons of good character—stealing independent comedy for corporate control. Chaplin’s plagiarism, United Artists’ rise: patterns of theft via scandals. Mafia’s Bioff/Roselli extortion: continuum from 1921. Without Arbuckle, no Keaton or Chaplin; his legacy stolen, mentors erased. Brooks’ defense ties to her own demolition—future article will connect. Modern ties: 2025 DEI headlines like “DEI Is Disappearing” mirror historical erasure. Our series demands reclamation.

- (Part 1 of “The Stolen Screen” (The Nickelodeon Gang) is here )

- (Part 2 of “The Stolen Screen” (Mabel Normand and Mack Sennett) is here )

- (Part 4 of “The Stolen Screen” (William Desmond Taylor and Mary Miles Minter) Coming Soon!

Lets remember Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle

© James Sewell 2026 – All rights reserved

A Personal Note from James Sewell

Fellow Ethnic Americans, my blood boils recounting Arbuckle’s destruction—a gentle soul framed, impoverished, dying young at 46. His wives’ sad fates—Minta’s lonely end in a actors’ home, Doris’ obscurity, Addie’s long widowhood—and vanished inheritance highlight the human tragedy. This theft of our screen mirrors the betrayal of our posterity: ancestors’ wilderness conquests squandered by outsiders. In 2026, as DEI erases us further, we must rise urgently—reclaim our inheritance, secure ethnic continuity. For our children, act now—James Sewell.