The Patent Theft and the Nickelodeon Takeover

Picture this: a shadowy cabal of immigrant opportunists, fresh from the gritty streets of New York’s nickelodeon dens, plotting to seize an entire industry born from the genius of a true American inventor. Whispers of stolen patents echo through dimly lit backrooms, leading to a trail of scandals, frame-ups, and unsolved murders that silenced the Ethnic American voices who dared to build something pure and innovative. This isn’t the plot of a forgotten silent film—it’s the real, gritty origin story of Hollywood, a saga of skullduggery, degeneracy, and corporate conquest that stripped the film world from its rightful creators and handed it to a lineage of power brokers whose influence lingers today, from film’s golden era moguls to modern figures like Harvey Weinstein. As an Ethnic American—aligned with the sturdy Protestant roots of the 1790 Naturalization Act, which envisioned a nation built by free white persons of good character—I see this as more than history; it’s a theft that demands reckoning. In this first installment, we’ll unravel the intrigue, backed by facts and receipts, before teasing a series of deep dives into the erased heroes: Mack Sennett and Mabel Normand, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Buster Keaton, William Desmond Taylor and Mary Miles Minter, DW Griffith and Frances Farmer. Buckle up; the truth is darker than ANY film noir thriller.

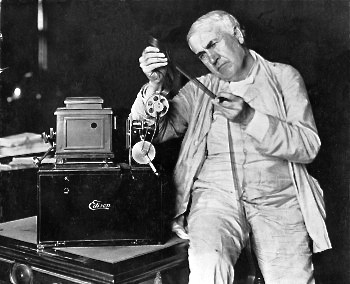

Our story begins not in the sun-soaked hills of Los Angeles, but in the inventive workshops of New Jersey, where Thomas Alva Edison, the epitome of Ethnic American ingenuity, ignited the flame of motion pictures

The Spark of Genius: Thomas Edison and the Birth of American Film

Born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio, to Samuel Ogden Edison Jr., of Dutch ancestry, and Nancy Matthews Elliott, of Scottish descent, Edison grew up in a modest household that valued hard work and innovation. From a young age, he displayed an insatiable curiosity, experimenting with chemistry and mechanics despite leaving formal schooling after just three months due to his teachers’ misconceptions about his hyperactivity. By age 12, he was selling newspapers on trains and operating a small laboratory in a baggage car, where a chemical fire nearly derailed his early career—literally.

Edison’s path to greatness was paved with perseverance. He held over 1,093 patents, transforming the world with inventions like the phonograph in 1877, which captured sound for the first time, and the practical incandescent light bulb in 1879, which illuminated homes and cities. His drive wasn’t about monopoly; it was about stewardship—protecting innovations that propelled America forward. In the late 1880s, inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope demonstrations, Edison turned his gaze to capturing motion. Working with his assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, he developed the Kinetograph camera and Kinetoscope viewer. On August 31, 1897, Edison patented the Kinetoscope, a peephole device that allowed individuals to watch short films, revolutionizing entertainment from static images to dynamic stories.

By 1893, his Black Maria studio in West Orange, New Jersey—the world’s first motion picture studio—churned out shorts like the Blacksmith Scene (watch this restored version on YouTube) and Fred Ott’s Sneeze (the first copyrighted film, view the original here), showcasing everyday wonders with technical mastery. These films were simple yet groundbreaking, capturing sneezes, dances, and animal movements to demonstrate the medium’s potential.

Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), formed in December 1908, wasn’t a greedy grab; it was a safeguard against chaos, ensuring quality amid rapid growth and licensing his technology to legitimate producers. This protective stance resonated deeply with Ethnic Americans, including my own family. My great-aunts moved to Florida to assist Edison at his winter estate, Seminole Lodge in Fort Myers, where he experimented with rubber plants during World War I to reduce America’s dependence on foreign supplies. They lived beyond 100, regaling us with stories of his kindness—how he treated employees like family—and unwavering dedication to American progress. Edison’s vision was pure: film as an extension of American innovation, free from exploitation; He as most Ethnic Americans was a builder, not a thief.

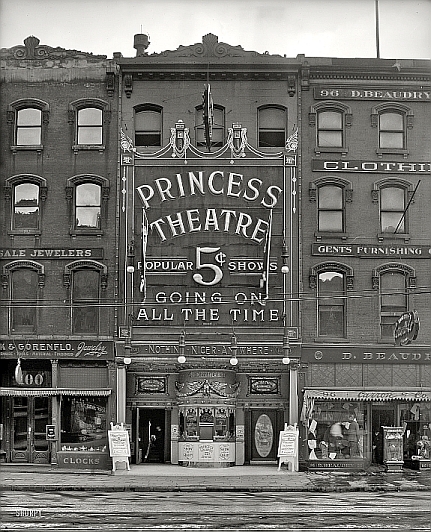

But darkness loomed. As nickelodeons—five-cent theaters (named for the nickel admission and the Greek word “odeion” for theater) popping up in converted storefronts in urban immigrant hubs—gained traction around 1905, a group of opportunists saw Edison’s patents as barriers to their schemes. These weren’t visionaries; they were gangsters who ran rackets in gambling, extortion, and whatever turned a profit, now eyeing film as their next hustle.

The early 1900s saw the explosion of nickelodeons, cheap theaters charging five cents for short films, often housed in converted storefronts in New York’s immigrant enclaves like the Lower East Side. By 1907, there were over 3,000 nickelodeons nationwide, drawing millions of working-class patrons daily. But behind the flickering screens lurked a network of operators who thrived on evasion and opportunism

The Great Patent Heist: Nickelodeon Gangsters Seize Control

These Nickelodeon gangsters dominated the trade, evading Edison’s patents through smuggling foreign tech, using bootleg cameras, and producing films without licenses. When Edison’s enforcers—hired detectives and lawyers—raided theaters and seized equipment, the gangsters fought back with lawsuits, bribery, and relocation. They also took over the nickelodeon studios themselves, often by aggressive buyouts or intimidation, and copied early Edison films without paying royalties—duping prints (illegally duplicating them) and sometimes adding notches or modifying perforations to make the films appear compatible with their unlicensed equipment, thus bypassing detection in Edison’s controlled system.

Historian accounts note that independents resorted to duping prints of licensed films (unauthorized copying) and other tricks to evade the trust’s restrictions, as the MPPC tried to control every aspect of production and distribution. Southern California in the early 1900s was a lawless frontier, akin to the Wild West, with vast open spaces, sparse population, and minimal law enforcement. Los Angeles, then a small city of about 100,000, was riddled with corruption, saloons, and vigilante justice, much like mining towns such as Bodie, California, which was notorious for shootouts and lawlessness. This remoteness allowed the gangsters to operate beyond Edison’s East Coast reach, as federal marshals were few and far between, and local authorities were often bribable. As one account notes, filmmakers fled to Hollywood to evade Edison’s “patent thugs,” establishing studios in a place where the law was as thin as the desert air.

A 1915 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Motion Picture Patents Co. dismantled the MPPC as an illegal trust under the Sherman Antitrust Act, but by then, the damage was irreversible—the gang had entrenched themselves in Hollywood. Edison sued rivals like American Mutoscope for infringement, highlighting the blatant theft, as documented in legal histories.

Let’s name them all, with their studios and legacies, substantiated by historical records (note: all were Jewish immigrants or of Jewish descent, as documented in Neal Gabler’s An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood):

- Adolph Zukor (Jewish): Born on January 7, 1873, in Ricse, Hungary, Zukor immigrated to the U.S. at age 16, starting as a furrier apprentice in New York. He entered the nickelodeon business in 1903, evading patents by using unlicensed projectors. In 1912, he founded Famous Players Film Company, focusing on feature-length films with stars like Mary Pickford. This merged with Jesse Lasky’s company in 1916 to form Famous Players-Lasky, precursor to Paramount Pictures, now Paramount Global.

- William Fox (Jewish): Born Wilhelm Fuchs on January 1, 1879, in Tolcsva, Hungary, Fox arrived in New York as an infant. He began in garment manufacturing before entering nickelodeons in 1904, openly defying Edison by running unlicensed theaters. In 1915, he established Fox Film Corporation in Fort Lee, New Jersey, before moving west. Known for Westerns with Tom Mix, it became 20th Century Fox in 1935 after merging with Twentieth Century Pictures, now part of The Walt Disney Company.

- Louis B. Mayer (Jewish): Born Lazar Meir on July 12, 1884, in Minsk, Russian Empire (now Belarus), Mayer immigrated to Canada as a child, then to Boston. Starting in scrap metal, he bought a nickelodeon in 1907, expanding despite Edison’s raids. In 1918, he moved to Los Angeles, co-founding Metro Pictures, which became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 1924 with Marcus Loew and Samuel Goldwyn, now owned by Amazon.

- Carl Laemmle (Jewish): Born on January 17, 1867, in Laupheim, Germany, Laemmle immigrated to Chicago in 1884, working as a bookkeeper before opening a nickelodeon in 1906. He founded Independent Moving Pictures (IMP) in 1909 to fight the MPPC, smuggling cameras and relocating to California. In 1912, IMP became Universal Film Manufacturing Company, opening Universal Studios Hollywood in 1915, now a Comcast subsidiary.

- Harry Cohn (Jewish): Born on July 23, 1891, in New York City to Jewish parents from Germany and Russia, Cohn started as a song plugger and vaudeville performer. With brother Jack, he founded CBC Film Sales in 1919, renaming it Columbia Pictures in 1924. Known for low-budget films, Columbia grew into a major studio, now Sony Pictures.

- Samuel Goldwyn (Jewish): Born Szmuel Gelbfisz on August 17, 1879, in Warsaw, Poland (then Russian Empire), Goldwyn immigrated to the U.S. in 1899, anglicizing his name. He co-founded Goldwyn Pictures in 1916 with the Selwyn brothers, merging into MGM in 1924. Later independent, he produced classics like Wuthering Heights.

- Marcus Loew (Jewish): Born on May 7, 1870, in New York City to Austrian-Jewish immigrants, Loew dropped out of school at 9, entering fur trading before nickelodeons in 1905. He built Loew’s Theatres chain and co-founded MGM in 1924 as its parent company.

- Jesse Lasky (Jewish): Born on September 13, 1880, in San Francisco to Jewish parents, Lasky started in vaudeville before partnering with Zukor in 1916 for Famous Players-Lasky, becoming Paramount.

- The Warner Brothers (Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack—Jewish): Born in Poland to Jewish parents—Harry on December 12, 1881; Albert in 1884; Sam in 1887; Jack on August 2, 1892—they immigrated to the U.S. Starting with a nickelodeon in 1903, they founded Warner Bros. in 1923, pioneering sound with The Jazz Singer, now Warner Bros. Discovery.

These men transformed Hollywood into their kingdom, sidelining Ethnic Americans through cutthroat competition. Their posterity still dominates, a direct line from patent theft to modern control. All these Companies run Hollywood to this day, more than 100 years later.

Amid the theft, Ethnic Americans like Mack Sennett created a haven of creativity at Keystone Studios, founded in 1912 in Edendale, California (now Echo Park).

The Ethnic American Bloom: Keystone and the Comedy Revolution

Sennett, born Michael Sinnott on January 17, 1880, in Danville, Quebec, to Irish Catholic parents, immigrated to Connecticut as a child. He started in vaudeville before joining Biograph Studios under D.W. Griffith, learning filmmaking. With backing from New York Motion Picture Company, Sennett built Keystone as a collaborative comedy factory, producing over 1,000 shorts by 1917. His “Keystone Kops” chases and pie fights became staples, defining American slapstick humor—without which the genre wouldn’t exist.

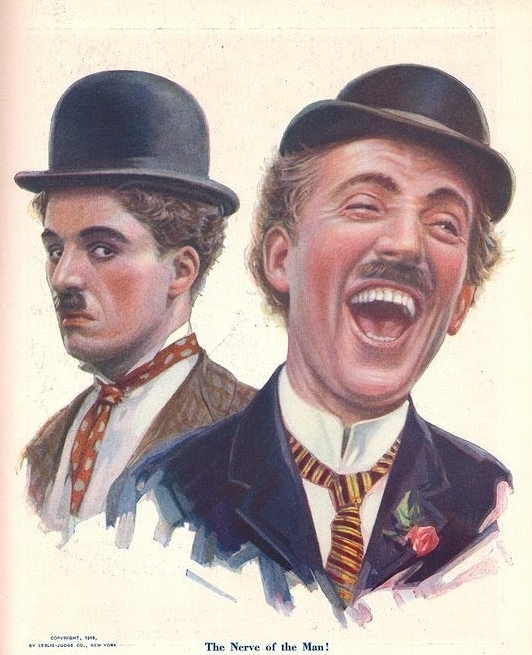

Mabel Normand, born Amabel Ethelreid Normand on November 9, 1892, in New Brighton, New York, to French-Canadian parents, was a director, writer, and star who brought fearless, physical comedy to the screen. Starting as a model, she joined Vitagraph in 1910, then Biograph, where she met Sennett. At Keystone, she directed and starred in films like Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914), often credited as the first Charlie Chaplin Tramp appearance. Normand’s wit and athleticism made her a trailblazer for women in film.

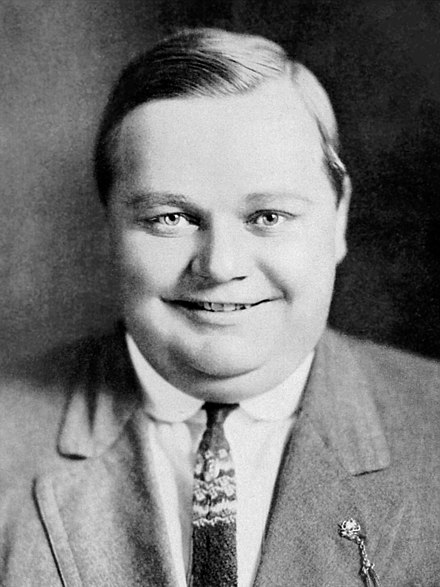

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, born March 24, 1887, in Smith Center, Kansas, to Scottish-American parents, began in vaudeville with his powerful voice and agile movements despite his size. Joining Keystone in 1913, he starred in hundreds of shorts, directing many and mentoring newcomers with kindness.

Arbuckle also launched Buster Keaton, born Joseph Frank Keaton on October 4, 1895, in Piqua, Kansas, to vaudeville parents. Arbuckle discovered him in 1917, casting him in The Butcher Boy and teaching film techniques. Keaton called Arbuckle his “greatest teacher.”

Together, they mentored Charlie Chaplin, who stole his Tramp from Billie Ritchie, as Ritchie accused and newspapers reported. Chaplin, born April 16, 1889, in London, joined Fred Karno’s troupe in 1908, where he met Scottish comedian Billie Ritchie (born William Hill Ritchie on September 14, 1878, in Glasgow). Ritchie had developed his “drunk tramp” character in the 1890s on British music halls, featuring baggy pants, oversized shoes, cane, mustache, and clumsy antics. Chaplin toured with Karno in the U.S. from 1910–1913, performing alongside Ritchie in sketches like “Mumming Birds,” where Ritchie’s tramp-like drunk was a highlight. If you click on the “Mumming Birds” link you can see how Chaplin even made it into a film— Billie’s Ritchie’s Act. When Chaplin joined Keystone in 1913, his Tramp debuted in 1914, strikingly similar to Ritchie’s act.

Ritchie publicly accused Chaplin of theft, stating in interviews that Chaplin “copied him” after seeing his performances. Newspapers like Variety reported the controversy, with Ritchie claiming the Tramp was his creation from the 1880s. Why do we think he stole it? The similarities are undeniable—costume, gait, sentimentality—and Chaplin’s Karno exposure provided opportunity. Ritchie even lent Chaplin clothes for his first Tramp film, per reports. Chaplin refined it but didn’t invent it, allowing him to outshine Ritchie, unknown to modern film goers, who died in 1921 from injuries on set.

Louise Brooks, born Mary Louise Brooks on November 14, 1906, in Cherryvale, Kansas—a small southeast Kansas town known for its cherry orchards and rural life—embodied Ethnic American resilience.

At 15, she moved to New York, joining the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in 1922. Founded in 1915 by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in Los Angeles, Denishawn was the cradle of American modern dance, blending ballet, ethnic European, and free-form styles to create a uniquely American art form, diverging from rigid European traditions. There, Brooks trained alongside Martha Graham, born May 11, 1894, in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, who became the “Mother of Modern Dance.” Graham, joining Denishawn in 1916, developed techniques emphasizing contraction and release, drawing from American pioneer spirit and psychology. Together, Brooks and Graham pioneered modern dance—an American creation that rejected ballet’s formality for expressive, grounded movements inspired by Native American, Asian, and European influences.

Brooks’ daring style and bob haircut sparked the Flapper craze, defining 1920s liberation in films like Pandora’s Box (1929). Without Brooks, there would be no Flapper era—yet today, Cherryvale’s local museum and Independence’s historical sites barely mention her, an egregious omission for Kansas’ greatest star. Jealousy from Marion Davies—William Randolph Hearst‘s long term girlfriend who he met in her teens, pushed her out, but the moguls ensured her memory faded.

But the gangsters couldn’t tolerate this independence, leading to the purges.

The Bloody Purge: Scandals, Murders, and Frame-Ups

The 1920s brought a wave of degeneracy and violence to crush Ethnic American rivals. Arbuckle’s 1921 frame in the Virginia Rappe case—where Rappe died from peritonitis after a party, with no evidence of assault—led to three trials and acquittal, but he was banned to remove a threat. William Desmond Taylor’s 1922 murder, found shot in his bungalow, entangled Normand (who was there earlier) and Mary Miles Minter, a 19-year-old ingenue competing with Pickford. Theories include drug deals or jealousy; no arrests, but careers ruined. Historical accounts note cover-ups in early Hollywood, from drug scandals to unsolved killings, influenced by mogul power.

Another tragic example of this sidelining was Frances Farmer, an outspoken Ethnic American actress from Seattle who rose to prominence in the 1930s with roles opposite stars like Bing Crosby and Cary Grant. Disillusioned with Hollywood’s star system and clashing with its controlling machine, Farmer turned to theater for creative freedom, but her struggles with alcohol led to arrests in 1942–1943.

After a courtroom outburst, she was committed to a sanatorium and later intermittently institutionalized by her mother for six years at Western State Hospital, amid sensationalized allegations of horrific abuses—including reoccurring gang rape, rat infestations, and even a lobotomy—stated in biographies like Shadowland and the 1982 film Frances Unmaking the myth of Frances Farmer. While verified history confirms her institutionalization stemmed from legal issues and family decisions, leading to profound mental health challenges, the lurid tales—such as years of gang rape driving her to utter mental illness—appear to be fabrications for dramatic effect, yet they underscore how the industry framed rebellious women as unstable to erase their influence. Farmer eventually sued for her freedom in 1953, but her career never recovered, exemplifying the decimation of Ethnic American talent who dared defy the moguls.

Mabel Normand’s health failed amid rumors of cocaine addiction; she died in 1930 at 37. Louise Brooks, The creator of the Flapper Movement, was pushed out by 1930, blacklisted for her independence. These weren’t accidents; they were tools to consolidate, as moral panics like the Hays Code masked the power grab.

Corporate Conquest: From Silent Mergers to Modern Monopolies

The takeover evolved through mergers. MGM formed in 1924 from Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer; Paramount from Famous Players-Lasky. The studio system—vertical integration of production, distribution, and exhibition—dominated the Golden Age, controlling stars with ironclad contracts. Antitrust in 1948’s Supreme Court Case The United States v. Paramount Pictures cracked it, forcing it’s divestiture. Today, Disney’s 2019 acquisition of Fox and Sony’s 1989 buy of Columbia echo the original grabs. The children of the Nickelodeon gangs play on.

Echoes of Degeneracy: From Early Moguls to Harvey Weinstein

The moguls’ legacy of abuse continued. Early Hollywood’s “casting couch” was systemic, with powerful men like Mayer and Cohn exploiting actresses through coercion and threats. Harvey Weinstein, born March 19, 1952, in New York, founded Miramax in 1979 and The Weinstein Company in 2005, producing Oscar winners like Pulp Fiction. But in 2017, over 80 women accused him of harassment, assault, and rape spanning decades. He used private investigators like Black Cube and NDAs to silence victims, echoing mogul tactics. As Neal Gabler notes, Weinstein emulated the original moguls he revered, seeing himself as a latter-day Cohn. This degeneracy traces back to the Nickelodeon gang’s power plays, where control was absolute. Nothing has changed although nothing can match the depravity of the originals moguls, not even Weinstein.

Punishing the Truth-Tellers: D.W. Griffith and Mel Gibson

Speaking truth often destroys. David W. Griffith, born January 22, 1875, in La Grange, Kentucky, to Confederate veteran parents, pioneered film techniques like close-ups and cross-cutting in The Birth of a Nation (1915); see the Original Film in 4K here. Innovative yet controversial for glorifying the KKK and racist portrayals, it sparked NAACP protests, riots, and career decline despite box-office success. It revived the KKK but led to Griffith’s marginalization by the 1920s.

Similarly, Mel Gibson, born January 3, 1956, in Peekskill, New York, directed The Passion of the Christ (2004), which grossed over $600 million but faced accusations of antisemitism for depicting Jewish leaders. His 2006 DUI arrest with antisemitic remarks led to Hollywood blacklisting, despite earlier successes like Braveheart. Both faced industry’s wrath for challenging norms, parallels drawn in cultural analyses. History Rhymes.

Teasing the Series: Reclaiming the Erased

This is just the overture. Future articles will spotlight:

- Mack Sennett and Mabel Normand – The Keystone Architects

- Roscoe Arbuckle and Buster Keaton – Mentors Framed and Forgotten

- William Desmond Taylor and Mary Miles Minter – Murder and Rivalry

- Frances Farmer – Forced Institutionalism and Gang Rape

Conclusion: Reclaim the Legacy

Hollywood was stolen—from Edison’s patents to today’s conglomerates—by gangsters whose tribesmen still reign. Ethnic Americans, it’s time to know and reclaim our story.

© James Sewell 2026 – All rights reserved

James Sewell here.

As I sit here watching another sunrise, I find myself reflecting on this saga I’ve pieced together—the theft of Edison’s inventions, the nickelodeon gangsters who fled to a lawless California to build empires on stolen patents, the frame-ups and purges that silenced Roscoe Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, Louise Brooks, Frances Farmer, and so many others—I’m left with one overriding conviction:

Hollywood was ours first. It was built by Ethnic Americans—people of Christian European stock who came here to create, invent, and entertain with warmth, ingenuity, and moral clarity. Thomas Edison wasn’t just an inventor; he was a steward of American progress. Mack Sennett and Mabel Normand weren’t just comedians; they were the architects of joy that defined a new art form. Roscoe Arbuckle wasn’t a scandal; he was a gentle giant railroaded so others could steal his crown.

The men who took it—through patent evasion, duped prints, aggressive mergers, and a willingness to destroy anyone who stood in their way—didn’t invent Hollywood. They conquered it. And the pattern never stopped. From the casting couch of the 1920s to Harvey Weinstein’s NDAs and black books, the same machinery of control, silence, and erasure has remained in place, now dressed up in modern corporate boardrooms and streaming algorithms.

Frances Farmer’s story, in particular, haunts me. An intelligent, defiant woman from the Pacific Northwest who dared to speak her mind and question the machine—framed as “unstable,” institutionalized, her life and career dismantled. Whether the most lurid tales of gang rape and lobotomy were exaggerated for sensationalism or not, the core truth stands: the industry had the power to label her mad, lock her away, and erase her talent when she refused to conform. That is not coincidence; that is a system.

We lost our industry to gangsters whose descendants still run it today. But history is not irreversible. The truth, once buried, can be exhumed. Every time we tell this story—accurately, unflinchingly, with names, dates, and receipts—we chip away at the myth they built. We remind people that Charlie Chaplin did not invent the Tramp; he refined someone else’s act after his mentors were removed. We remind people that Keystone was the real birthplace of American comedy, not United Artists. We remind people that Edison’s patents were protected genius, not oppressive monopoly.

This series is my small contribution to that reclamation.

To every Ethnic American reading this: know your history. It wasn’t taken because it was inferior. It was taken because it was dangerous—too independent, too collaborative, too rooted in the values of the 1790 Act and the pioneer spirit.

They feared what we could build if left alone. So they didn’t let us stay alone.

But the screen is wide open again. We can still tell our own stories. We can still name the thieves. And we can still laugh, create, and remember—with the same warmth Roscoe once brought to every frame.

The gangsters may have stolen the kingdom, but they never owned the light that shines through the projector.

That light is still ours.

Let’s keep it burning.

— James Sewell January 2026